© Peter Andersen, Schott

© Peter Andersen, Schott

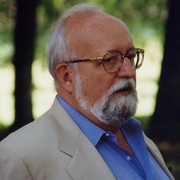

Krzysztof Penderecki

Polish composer and conductor born 23 November 1933 in Debica; died 29 March 2020 in Krakow.

Born in Debica, Poland in 1933, Krzysztof Penderecki took up both piano and violin at an early age. From the age of 18, he studied composition with Franciszek Skolyszewski at the Krakow Conservatory, alongside studies of philosophy, history, and literary history at the university in the same city. Starting in 1954, he undertook further study of composition with Artur Malawski, and later with Stanislas Wiechowicz (after the death of Malawski in 1957), at the Krakow Academy of Music.

Following the premiere of Strophen in 1959 at Warsaw Autumn, Penderecki gained recognition as a significant figure in contemporary music. Subsequent works, such as Dimensionen der Zeit und der Stille (1959-60), Fluorescences (1961-62), and String Quartet No. 1 (1960), cemented his reputation internationally.

Penderecki’s music up to the late-1970s is replete with sonic effects while remaining compositionally economical. It is characterised by powerful gestural figures constructed from “ultra-chromatic” clusters, glissandi, and chance elements, as well as by the use of novel extended techniques (notably in the strings). The radicalism and novel timbres in works such as Emanations (1959), Anaklasis (1960), Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima (1960), Dies Irae (Auschwitz Oratorium) (1967), Polymorphia (1961), and De natura sonoris No. 1 (1966) led to comparisons with the works of Xenakis and Ligeti. However, in contrast to these two composers, Penderecki frequently drew inspiration from his religious convictions, as evidenced by sacred works such as Stabat Mater (1962), which would later be incorporated into St Luke Passion (1966) and Utrenja (1969).

Later, without diminishing his standing as a pre-eminent composer, Penderecki gradually abandoned the avant-gardist elements in his musical language, adopting a musical style which would draw considerable criticism from his peers but which also brought about a much broader acceptance of his works. This new period was marked by neo-tonality, in the form of a post-romantic, even Brahmsian style — as in Requiem (2005) — which resembled New German Simplicity (albeit with a religious dimension, an element that remained present throughout his career).

While teaching at the Essen Conservatory (1966-68), Penderecki composed his first opera, The Devils of Loudun, a work which counts among the crowning achievements of his first period, premiered in 1969 at the Hamburg Opera and subsequently toured internationally to great acclaim. Three further operas followed: Paradise Lost after John Milton, premiered in 1978 in Chicago; The Black Mask, based on a play by Gerhart Hauptmann, premiered in 1986 at the Salzburg Festival; and Ubu Rex after Alfred Jarry, premiered in Munich in 1991.

Penderecki was the recipient of numerous accolades, notably for his concertos, chamber works, and vocal music. He was also awarded honourary doctorates and professorial chairs from universities around the world.

- 1959: First Prize in the Second Competition for Young Polish Composers for Strophes, Emanations, and Psalms of David

- 1961: UNESCO Prize for Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima

- 1968: Italia Prize for Dies Irae (Auschwitz Oratorium)

- 1966: Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen Grand Prize for St Luke Passion

- 1967: Italia Prize for St Luke Passion

- 1967: Sibelius Gold Medal

- 1970: Union of Polish Composers Prize

- 1977: Arthur Honegger Prize for Magnificat

- 1983: Sibelius Prize from the Wihouri Foundation (Poland)

- 1985: Lorenzo Magnifico Prize

- 1990: Great Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- 1990: Chevalier Saint Georges

- 1992: Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition for Symphony No. 4: Adagio

- 1992: Austrian Medal of Arts and Sciences

- 1993: “Distinguished Citizen Fellowship” from Indiana University, Bloomington

- 1993: UNESCO Prize

- 1993: Order of Cultural Merit from the Principality of Monaco

- 1995: Member of the Dublin Royal Academy of Music

- 1995: Citizen of Honour of the City of Strasbourg

- 1995 and 1996: Nominated for Emmy Awards by the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences

- 1998: Composition Prize from the Promotion Association of European Industry and Trade

- 1998: “Foreign Honorary Membership” of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- 1998: Corresponding Member of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts, Munich

- 1999: City of Duisburg Prize (Germany)

- 1999: Honourary Member of the Vilnius Festival

- 2000: Cannes Classical “Composer of the Year” Award

- 2000: Honourary Member of the Vienna Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

- 2001: Prince of Asturias Award for the Arts

- 2001: Honourary Member of the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts

- 2002: Romano Guardini Prize from the Catholic Academy in Bavaria

- 2003: Citizen of Honour of the City of Debica (Poland)

- 2003: Eduardo M. Medal from the Conservatorio de Música del Principado Asturias

- 2003: Honourary Director of the Prince of Asturias Foundation Choir

- 2003: Honourary President of the “Apoyo a la Creación Musical” Cultural Foundation

- 2004: Praemium Imperiale

- 2006: Order of the Three Stars (Latvia)

- 2006: Order of the White Eagle (Poland)

- 2008: Honourary Professor at Komitas Conservatory, Erevan (Armenia)

- 2008: Gold Medal from the Armenian Ministry of Culture

- 2008: Polish “Eagle” (Academy Award) for the soundtrack for the film Katyń

- 2009: Medal of Honour from the Republic of Armenia for strengthening the relationship between Poland and Armenia, and for his scenic works.

- 2011: Super Wiktor Award from Polish Television

- 2012: Lifetime Achievement Award at the International Classical Music Awards

- 2012: European University Viadrina Prize, Frankfurt an der Oder (Germany)

- 2012: Glocal Hero Award from the Transatlantyk Festival Poznan (Music and Film) for Elzbieta and Krzysztof Penderecki (Poland)

- 2013: “Paszport Polityk” Prize from Polityka magazine (Poland)

- 2013: Citizen of Honour of the City of Krakow

- 2014: Gold Medal from the City of Erevan (Armenia)

- 2014: Honourary Member of the Union of Armenian Composers

- 2014: “Diamond Laurel of Abilities and Competence” from the City of Zabrze (Poland)

- 2014: Honourary Member of the Graz Musikverein (Austria)

- 2014: Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana, First Class (Estonia)

- 2015: Honourary President of the Union of Polish Composers

- 2015: Per Artem ad Deum Medal from the Pontifical Council of Culture

- 2017: Erazm and Anna Jerzmanowski Prize from the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences

- 2018: Great Cross with Star of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

© Ircam-Centre Pompidou, 2014

Sources

- Éditions Schott

By Jacques Amblard

This text is being translated. We thank you for your patience.

Durant les années soixante, Penderecki s’attache notamment, de façon singulière, à l’effectif de l’orchestre à cordes. C’est d’ailleurs Thrène à la mémoire des victimes d’Hiroshima (1960) qui lance définitivement le compositeur dans sa carrière internationale. Il y a là, tout d’abord, quelque « inclination instrumentale polonaise ». Sinfonietta (1956) de Serocki, Funeral music (1956-1958) de Lutoslawski, Symphony for strings and percussions (1959) de Gorecki, ou encore Monosonata (pour 24 instruments à cordes solistes) de Boguslaw Schäffer magnifient toutes presque seulement les instruments à archet1.

À ceux-ci, Penderecki avait déjà confié ses Emanations2 en 1958. Mais il faut attendre la célèbre Thrène pour qu’il élabore son écriture caractéristique des cordes. C’est elle qu’on retrouvera, assez peu changée, dans le premier Quatuor (1960), dans Polymorphia (1961) et Canons (1962). L’écriture renonce aux portées et autres notations classiques, et s’attache au seul critère du timbre. Sons et bruits sont désormais esthétiquement égaux. Penderecki emploie force clusters. Il s’agit « d’accords » modernes et particulièrement dissonants qui rassemblent des notes très proches, ce qui engendre des frottements particulièrement sévères. L’appréhension de toute note finit par disparaître et c’est un timbre global, singulièrement amplifié, qu’on entend, d’autant plus radical et strident, dans Thrène, que le cluster y est volontiers choisi dans l’aigu. Varèse commençait à employer de petits clusters de quelques demi-tons consécutifs, dans la première moitié du siècle, lui aussi déjà pour démontrer son attachement au seul timbre des instruments et pour ce faire pour « annuler les hauteurs » en faisant frotter celles-ci les unes contre les autres. Penderecki, et la jeune école polonaise ont connu – ne serait-ce qu’indirectement – ce type de précédent varésien, ou peut-être celui des Américains Ives et Cowell, musiciens de légèrement moindre envergure peut-être, mais qui avaient employé les clusters de façon plus franche encore, à la même époque que Varèse et même légèrement auparavant.

Le « cri d’horreur » initial de Thrène, particulièrement saisissant, et celui-là même qui a offert à Penderecki sa première célébrité, est un cluster de cordes dans l’aigu joué le plus fortement possible. C’est un cluster en quarts de tons et non plus seulement en demi-tons comme dans la première moitié du siècle, donc plus « abrasif » encore. Voici un geste « radical moderne » dans sa plus simple expression : c’est bien là d’ailleurs ce qui semble le talent de Penderecki – qu’il partage sans doute avec Ligeti – que de présenter des « nouveautés techniques ou esthétiques » comparables à celles de ses contemporains, mais d’une façon plus évidente, emblématique.

Thrène, œuvre « bruitiste » comme un an plus tard Polymorphia, fait aussi entendre de très caractéristiques « sirènes » d’instruments à cordes : les sons évoluent non sur des échelles de notes, mais selon des glissades continues (des « glissandos »). Les « bruits de sirènes » ainsi engendrés instillent une impression d’alarme claire, évidemment expressive. On peut y retrouver les sirènes chères à Varèse, celles qui résonnent déjà dans Amériques (1918-1921), puis Ionisation (1928). Varèse les employait pour les mêmes raisons (l’annulation de la note, notamment des notes séparées arbitrairement par l’échelle tempérée en demi-tons) à ceci près qu’il introduisait dans l’orchestre de réelles sirènes à manivelle. Au-delà, il est impossible de ne pas penser au célèbre Metastasis (1954) de Xenakis, où résonnent déjà des clusters de cordes mais aussi de vastes mouvements d’éventails glissés. Il est possible que Penderecki ait eu vent, au moins indirectement, de cette œuvre. Peu avant Thrène, il écrivait ainsi ses Anaklasis (1959-1960) qui rappellent plus encore Metastasis, par leur écriture ou ne serait-ce que leur effectif d’orchestre à cordes muni de percussions, sans même parler de leur nom philhellène.

Anaklasis entérine la rupture définitive avec la première écriture sérielle d’étudiant. Cependant, trois décennies encore, le compositeur pourra choisir certains thèmes qui, pour être des séries dodécaphoniques au sens strict (employant dans leurs douze notes les douze demi-tons de l’échelle tempérée), n’en évolueront pas moins selon une esthétique différente. Car les autres plans sonores n’obéiront à aucune logique sérielle. Et l’esthétique sera parfois même tonale : de même Richard Strauss, dans « De la science », extrait d’Ainsi parlait Zarathoustra (1896), pouvait déjà choisir une « série » pour sujet de fugato, dans un langage demeurant pourtant romantique.

On retrouve dans Anaklasis, outre l’univers xénakien, la « micropolyphonie » de Ligeti. Sans parler d’influence, on peut gager que les deux compositeurs évoluent de façon parallèle. Ils utilisent des idées qui « sont dans l’air du temps ». Dans Apparitions (1958-1959) ou Atmosphères (1961), donc exactement à la même époque, le Hongrois choisit lui aussi une écriture des pupitres extrêmement divisée, des canons multipliés presque jusqu’au phénomène de généralisation statistique, des clusters et globalisations des paramètres de hauteurs, donc des « notes approximatives », si l’on veut. Simplement, Ligeti conserve, lui, le système de notation traditionnelle.

Mais le règne du degré, pour ces compositeurs, a vécu. Place désormais au « geste », plus global. Si l’on souffre cette métaphore mathématique, on ne s’attache plus à la fonction, mais seulement à sa dérivée. Surtout, et comme dans des œuvres comparables de Xenakis, ce sont de nouveaux et saisissants effets de masse qui sont recherchés. « L’esthétique chambriste » de la modernité, celle du Marteau sans maître de Boulez (1954), issue de Pierrot lunaire (1912) de Schoenberg, que même Stravinsky – pourtant d’abord auteur de grands chefs-d’œuvre pour vaste orchestre tels le Sacre du printemps de 1913 – avait adoptée, semble être abandonnée.

On retrouve généralement, dans les œuvres ultérieures de Penderecki, un même goût pour le gigantisme, d’autant plus à partir de Fluorescences (1962), première œuvre à s’autoriser l’octroi des vents, et donc « pièce pour grand orchestre » proprement dite. Les vents, eux aussi, sont alors volontiers groupés en clusters et évoluent de façon « globale ».

Une seconde étape dans la carrière de Penderecki semble franchie lorsque le musicien élabore un nouveau style vocal. Dans le Stabat mater (1962) puis surtout la Passion selon saint Luc (1965-1966), l’éternelle inspiration de la liturgie – de façon naturelle chez ce musicien croyant –, semble justifier, comme souvent au cours de l’histoire de la musique, un relatif « retour esthétique ». Si les clusters y demeurent parfois, notamment appliqués aux chœurs, certains numéros des œuvres apparaissent sinon tonals, du moins « polaires » : une simple note, un « socle », est souvent identifiable. La note sol semble le centre des numéros 1, 6, 11 et 13 de la Passion. Sous ses pieds, l’auditeur sent à nouveau ainsi le « sol » traditionnel de la musique, en quelque sorte. Et même si l’harmonie tonale reste absente, on en termine par des accords parfaits (tels de glorieux indicateurs de la fin). Les choristes ou chanteurs solistes retrouvent des échelles tempérées en demi-tons et des lignes conjointes : vocales.

Ceci s’applique même aux cordes graves qui inventent leur futur archétype pendereckien : volontiers en mouvement chromatique, lentes, isolées du reste de l’effectif, souvent seules au début de l’œuvre, comme dans l’exposition sombre d’un sujet de fugue dans le grave. Ceci fera tout l’intérêt, encore, de la passacaille de la Troisième symphonie (1988-95). Son début sépulcral étrennera sombrement le film de Scorsese Shutter island (2010). On y retrouve l’univers noir de Chostakovitch. D’ailleurs cette passacaille ne répond-elle pas à celle de la huitième symphonie du Russe (1943) ?

Surtout, Penderecki invente une écriture chorale religieuse : elle aussi puissamment emblématique, exemplaire. Il distille l’essence, le timbre de cette musique éternelle en accentuant la fascination de ses graves et ainsi de ses pompes : dans le In pulverem mortis de la Passion, le chœur des basses tient en pédale la note la plus grave dont il est capable (un ré). Bourdonne alors quelque « mystique sépulcrale » à l’effet comparable à ces ultra graves entonnés à l’unisson par les moines tibétains. Au-delà, au début de la Passion, les tutti de chœurs fortissimo sont soulignés non seulement par les cuivres les plus tonitruants, mais aussi par les graves du pédalier des orgues en plein jeu, puis de gigantesques clusters à l’instrument d’église : Penderecki magnifie la puissance sonore paradoxalement terrifiante, «l’effet d’outre-tombe» des œuvres d’église. Cet effet «gothique» sourdait déjà dans les Passions et grands pièces d’orgue de Bach puis dans les requiems classiques et romantiques.

L’écriture des chœurs, quand elle abandonne les accords de douze sons, ou à l’opposé, les accords tonals de trois sons, choisit parfois, souvent, de simples quintes à vide, voire unissons – encore à la fin du Dies illa (2014). Elle engendre ainsi un effet de crudité médiévale, rappelant les Carmina burana (1936) de Carl Orff, d’autant plus dans la nuance forte souvent choisie. Ce « lyrisme gothique » à la Orff parcourra bien des œuvres vocales ultérieures, notamment le chef-d’œuvre Ecloga VIII de 1972 ou, même en version quasi néo-tonale, jusqu’aux premières accords des chœurs sombres, graves, de Dies illa (2014).

Mais quelle « version quasi néo-tonale » ? Voilà : à la fin des années 1970, montrant encore une « exemplarité » dans ses choix, Penderecki a pris clairement le tournant postmoderniste. Dans l’opéra Paradise lost (1976-1978), le Concerto pour violon (1976-1977) ou encore la Symphonie n° 2, le langage devient subitement un exemple clair de post-romantisme. Penderecki, homme apparemment – si l’on veut – « simple et sincère » et dès lors éventuellement « radical », choisit soudain une harmonie et des lignes chromatiques wagnériennes, ou plus précisément – plus gravement, sombrement – à la Chostakovitch.

Au début des années 1980, enfin, après cette violente antithèse postmoderne, il fait la synthèse de ses deux premiers styles et peut juxtaposer – plutôt que toujours bien « mélanger » – les parties ici tonales, là atonales et crissant de clusters. Si les opéras, comme Le masque noir (1984-86) ou Ubu roi (1990-1991), pousseront surtout la partie atonale, ponctuellement, comme pour suivre l’exemple noir-expressionniste de Berg, cette dialectique (tonalité versus atonalité), certes un peu apaisée, dynamisera encore le Concerto pour accordéon (2017). Auparavant, le fameux Requiem polonais (1980-1984) témoigne déjà de cette périlleuse macro-synthèse. Il y intègre son préalable Lacrimosa (1980), tonal et straussien, et dont « l’archétype de cordes graves en évolution lente et chromatique », évoqué plus haut, semble avoir finalement contaminé toutes les parties. Cette pièce, typique, est devenue comme le symbole d’une Pologne musicienne éplorée, pleureuse des morts, symbole qu’on retrouve dans la célébrissime Troisième symphonie du compatriote Gorecki (1976), à la mémoire des victimes de la Shoah. Ce symbole sembla suffisamment fort, prégnant, pour que Penderecki écrive, jusque deux ans avant sa mort, un Lacrimosa n°2 (2018).

Ce Lacrimosa était une commande de Solidarność. Il montre bien ce qu’aura été l’œuvre de Penderecki, une œuvre ancrée dans l’histoire politique de son pays. Les cuivres y furent souvent présents, comme en grandes pompes officielles, jusqu’à la Fanfare pour la Pologne indépendante (2018). Ce fut aussi celle d’un Polonais ancré dans sa culture catholique, fervente, persistante, et dès lors souvent très volontiers vocale et liturgique, phénomène singulier au sein d’un XXe siècle plutôt matérialiste et scientiste, au point que rares furent les contemporains, tels Messiaen et Pärt, qui ont pu rivaliser avec le Polonais en matière d’illumination religieuse chrétienne.

Cette œuvre solennelle privilégiait les grandes formes, les effectifs gigantesques, xénakiens. Elle présentait de grands emblèmes. Ce souci de clarté favorisait les contrastes et poussait, par exemple, les aigus dans Thrène et autres pièces pour orchestre à cordes ultérieures, les graves dans les pièces liturgiques. Cette œuvre morale (puisque religieuse), didactique, exemplaire, conquit un large public. Elle présenta, voire expliqua, aussi bien que celle de Ligeti, la modernité musicale au monde. Antoine Goléa évoque Thrène, donnée en novembre 1962, salle Pleyel, par l’Orchestre de la Radiodiffusion de Varsovie : « les auditeurs [dont de nombreux jeunes] l’ont tellement bien supportée qu’ils l’ont bissée ; c’était le véritable grand public2 ».

Partant, le musicien, certes surtout au siècle précédent, jouit d’un succès et d’honneurs considérables, rares pour un compositeur – la moitié du temps – atonal. Certaines instances politiques, qui semblaient elles-mêmes s’être résolues à la « nécessité de la révolution atonale », semblèrent lui savoir gré de leur avoir « facilité » l’écoute de cette « modernité nécessaire ».

Rappelons, pêle-mêle, que Penderecki reçut le Prix de l’Unesco en 1961, une commande de l’ONU, ou du pourtant conservateur Festival de Salzbourg, que son Concerto pour violon, son Second Concerto pour violoncelle, furent créés respectivement par Stern et Rostropovitch, que Ronald et Nancy Reagan lui écrirent personnellement pour l’anniversaire de ses cinquante ans, qu’il eut droit aux chaleureuses félicitations de son certes compatriote, le pape Jean-Paul II. Avançons encore qu’outre son aspect spirituel, solennel, et donc particulièrement agréable, voire utile aux politiques en tant que catalyseur de grands rassemblements populaires, son œuvre eut le mérite singulier, non seulement de s’expliquer elle-même, par son sens du choix, mais de se théâtraliser, ce qui ne signifie pas exactement se vendre.

Ne donnons qu’un exemple. La violence des clusters aigus concernait nombre d’œuvres de la seconde moitié du XXe siècle, notamment un obscur 8’37’’ – par allusion au 4’33 de Cage (1952) – d’un non moins obscur et jeune « Penderecki ». L’œuvre et notamment sa partition, a priori, pouvaient paraître à ce point ésotériques que la douane polonaise y a cherché quelque rapport d’espionnage en langage codé. C’est alors que ce compositeur peu connu a rebaptisé son œuvre Thrène à la mémoire des victimes d’Hiroshima. Elle fut alors remarquée et bientôt recommandée par l’Unesco.

Ainsi, le compositeur s’est placé du côté du public et des instances politiques, donc du point de vue de la réception de la modernité dérangeante. Le public y entendait du chaos ? Dès lors, il semblait simple de rappeler ce chaos dans le titre et de faire ainsi, de cette œuvre bientôt célèbre, une gigantesque catharsis du chaos du monde. Penderecki, coup de maître, composait avec « l’horizon d’attente du public », selon la recommandation du philosophe Jauss3, en même temps qu’il justifiait l’idée d’Adorno selon laquelle, après les horreurs de la seconde guerre mondiale, l’art ne pourrait plus jamais se montrer affirmatif4.

- Pour plus de détails, voir l’ouvrage de Barbara Malecka-Contamin, Krzysztof Penderecki. Style et matériaux, Paris, Kimé, 1997.

- « Le public devant certains aspects de la musique contemporaine », in Pour une sociologie de la musique contemporaine, Semaines Musicales Internationales de Paris, 1962, p. 15.

- Concept central de Hans Robert Jauss, Pour une esthétique de la réception, Paris, Gallimard, 1978.

- « Une culture ressuscitée après Auschwitz est un leurre et une absurdité. », Theodor Widesmund Adorno, « Les fameuses années vingt », in Modèles critiques : interventions, répliques, Paris, Payot, 2003, p. 59.

Sources

Parcours écrit en 2008, revu en 2022.

© Ircam-Centre Pompidou, 2008

- Solo (excluding voice)

- Capriccio per Siegfried Palm for solo cello (1968), 6 mn, Schott

- Capriccio for solo tuba (1980), 6 mn, Schott

- Cadenza version for solo viola by Christiane Edinger (1984), 8 mn, Schott

- Cadenza for solo viola (1984), 8 mn, Schott

- Per Slava for solo cello (1985-1986), 6 mn, Schott

- Prélude for clarinet in Bb solo (1987), 2 mn, Schott

- Divertimento for solo cello (1994, 2006), 17 mn, Schott

- Sarabanda for viola (2000, 2009), 3 mn, Schott

- Capriccio for solo violin (2008), 3 mn, Schott

- Tanz for violin (2009), 2 mn, Schott

- Tanz for viola (2010), 2 mn, Schott

- Violoncello totale for cello (2011), 6 mn, Schott

- Capriccio per Radovan "Il sogno di un cacciatore", for horn (2012), 4 mn, Schott

- La Follia for violin (2013), 13 mn, Schott

- Suite for cello (1994-2013), 20 mn, Schott

- Tempo di valse for viola (2013), 3 mn, Schott

- Tanz viola version (2016), 2 mn, Schott

- Chamber music

- Sonate for violin and piano (1953), 9 mn, Schott

- Tre miniature for clarinet and piano (1956), 3 mn, Schott

- Miniatures for violin and piano (1959), variable, PWM (Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne)

- Quartetto per archi n°1 (1960), 8 mn, PWM (Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne)

- Quartetto per archi n° 2 (1968), 7 mn 30 s, Schott [program note]

- Der unterbrochene Gedanke for string quartet (1988), 3 mn, Schott

- Streichtrio for violin, viola and cello (1990), 12 mn, Schott

- Quartett for clarinet and string trio (1993), 20 mn, Schott

- Sonata n° 2 for violin and piano (1999), 35 mn, Schott

- Sextett for clarinet, horn, piano and string trio (2000), 30 mn, Schott

- Kadenz for the Brandenburg Concerto in G major by Johann Sebastian Bach, for viola, cello and harpsichord (2006), 2 mn, Schott

- Serenata for three cellos (2007), 4 mn, Schott

- Quartetto per archi n° 3 (2008), Schott

- Duo concertante for violin and double bass (2010), 6 mn 10 s, Schott

- Sinfonietta n° 3 for string quartet (2008-2012), 15 mn, Schott

- Quintetto per archi for string quintet, after String Quartet No.3 (2013), 15 mn, Schott

- Ciaccona In memoriam Giovanni Paolo II, transcription for six cellos (2015), 7 mn, Schott

- Quartetto per archi no. 4 (2016), 15 mn, Schott

- Instrumental ensemble music

- Epitafium Artur Malawski in memoriam for strings and timpani (1957-1958), 4 mn, Schott

- Emanationen for two string orchestras (1958-1959), 8 mn, Schott

- Anaklasis for strings and percussion (1959-1960), 9 mn, Schott

- Threnos Den Opfern von Hiroshima, for 52 string instruments (1960), 8 mn, Schott

- Polymorphia for 48 string instruments (1961), 10 mn, Schott

- Aria [et] Deux menuets for string orchestra (1962), 3 mn 35 s, Schott

- Fluorescences for orchestra (1961-1962), 16 mn, Schott

- elec Kanon for string orchestra and magnetic tape (1962), 10 mn, Schott

- Drei Stücke im alten Stil based on the music for the film Die Handschrift von Saragossa, for string orchestra (1963), 6 mn, Schott

- De natura sonoris n° 1 for orchestra (1966), 8 mn, Schott

- Uwertura pittsburska for wind orchestra, percussion and keyboards (1967), variable, Peters

- Actions for jazz ensemble (1971), 17 mn, Schott

- De natura sonoris n° 2 for orchestra (1971), 10 mn, Schott

- Preludium for wind, percussion and double bass orchestra (1971), 8 mn, pas d'éditeur

- Intermezzo for 24 stringed instruments (1973), 7 mn, Schott

- Sinfonie n° 1 for orchestra (1972-1973), 30 mn, Schott

- Przebudzenie Jakuba for symphony orchestra (1974), between 8 mn and 12 mn, Schott

- Adagietto from Paradise Lost for orchestra (1979), 5 mn, Schott

- Sinfonie n° 2 "Christmas Symphony" for orchestra (1979-1980), 36 mn, Schott

- Adagio Sinfonie n° 4 for large orchestra (1989), 33 mn, Schott

- Sinfonietta per archi for string orchestra (2013, 1990-1991), 12 mn, Schott

- Sinfonie n° 5 "Coréenne", for orchestra (1991-1992), 35 mn, Schott

- Entrata for brass and timpani (1994), 4 mn, Schott

- Musik aus «Ubu Rex» for orchestra, establishment by Henning Brauel (1994), 25 mn, Schott

- Burleske Suite aus Ubu Rex for large wind orchestra, establishment by Henning Brauel (1995), 16 mn, Schott

- Sinfonie n° 3 for orchestra (1988-1995), 50 mn, Schott

- Serenade für Streichorchester (1996-1997), 10 mn, Schott

- De profundis from Seven Gates of Jerusalem, version for string orchestra (1998), 7 mn, Schott

- Luzerner Fanfare for 8 trumpets and percussion (1998), 6 mn, Schott

- Fanfarria Real for orchestra (2003), 5 mn, Schott

- Ciaccona In memoria Giovanni Paolo II, for string orchestra (2005), 12 mn, Schott

- Ciaccona from Polnisches Requiem, In memoria Giovanni Paolo II, for string orchestra (2015, 2005), 7 mn, Schott

- Danziger Fanfare for brass, timpani and percussion (2008), 2 mn, Schott

- Sinfonietta n° 3 leaves from an unwritten diary, version for string orchestra (2012, 2008), 15 mn, Schott

- Ciaccona In memoria Giovanni Paolo II, for violin and viola (or cello) (2009), 7 mn, Schott

- Prelude for Peace for brass, timpani and percussion (2009), 4 mn, Schott

- De natura sonoris n° 3 for orchestra (2012), 7 mn, Schott

- Adagio from Sinfonie n° 3 for orchestra (2013, 1995), 14 mn, Schott

- Adagio from Symphony No.3 for string orchestra (2013), 14 mn, Schott

- Polonaise for orchestra (2015), 7 mn, Schott

- Fanfare for the independent Poland for seven brass instruments, timpani and percussion (2018), 60 s, Schott

- Polonaise for orchestra (2018), 2 mn, Schott

- Concertant music

- Fonogrammi for flute and chamber orchestra (1961), 7 mn, Schott

- Capriccio for oboe and 11 string instruments (1964), 7 mn, Schott

- Sonata for cello and orchestra (1964), 10 mn, Schott

- Capriccio for violin and orchestra (1967), 10 mn, Schott

- Concerto for cello and orchestra (1967, 1972), 20 mn, Schott

- Partita for harpsichord, electric guitar, bass, harp, double bass and orchestra (1971, 1991), 19 mn, Schott

- Concerto for violin and orchestra (1976-1977), 40 mn, Schott

- Concerto for cello and orchestra n° 2 (1982), 35 mn, Schott

- Concerto for viola (or cello or clarinet) and orchestra (1983), 22 mn, Schott

- Concerto for viola (or cello or clarinet), version for chamber orchestra, strings, percussion and celesta (1983-1984), 22 mn, Schott

- Concerto for flute (or clarinet: 1995 version) and chamber orchestra (1992-1993, 1995), 25 mn, Schott

- Sinfonietta n° 2 for clarinet and strings (1994), 20 mn, Schott

- Metamorphosen Concerto for violin and orchestra n° 2 (1992-1995), 35 mn, Schott

- Kadenzen for the concerto for trumpet and orchestra by Joseph Haydn in Eb major, for solo trumpet with accompaniment of two horns (1999), 4 mn, Schott

- Musik for recorders, marimba and strings (2000), 13 mn, Schott

- Concerto Resurrection, for piano and orchestra (2001, 2007), 38 mn, Schott

- Concerto Grosso for three cellos and orchestra (2000-2001), 35 mn, Schott

- Largo for cello and orchestra (2007, 2003), 28 mn, Schott

- Concerto grosso n° 2 for five clarinets and orchestra (2004), 17 mn, Schott

- Adagietto from Paradise Lost, version for English horn and string orchestra (2007), 5 mn, Schott

- Concerto Winterreise, for horn and orchestra (2007-2008), 16 mn, Schott

- Concertino for trumpet and orchestra (2015), 12 mn, Schott

- Concerto for accordion and orchestra (2017), 22 mn, Schott

- Concerto doppio version for flute, clarinet and orchestra (2017), 22 mn, Schott

- Vocal music and instrument(s)

- Aus den Psalmen Davids for mixed choir and ensemble (1958), 10 mn, Schott

- Strophen for soprano, spoken voice and ensemble (1959), 8 mn, Schott

- Dimensionen der Zeit und der Stille for mixed choir of 40 voices and percussion and string ensemble (1959-1960, 1961), 15 mn, Schott

- Cantata in honorem Almae Matris Universitatis Iagellonicae sescentos abhinc annos fundatae for two mixed choirs and orchestra (1964), 6 mn, Schott

- stage Najdzielniejzy z rycerzy Children's opera in three acts (1965), 60 mn, Inédit

- Passio Et Mors Domini Nostri Jesu Christi Secundum Lucam for soprano, baritone, bass, narrator, children's choir, two mixed choirs and orchestra (1965-1966), 1 h 20 mn, Schott

- Dies Irae Oratorium ob memoriam in perniciei castris in Oswiecim necatorum inexstinguibilem reddendam, for soprano, tenor, bass, mixed choir and orchestra (1967), 22 mn, Schott

- Die Teufel von Loudun opera in three acts (2012, 1968-1969), 1 h 50 mn, Schott

- Utrenja I Grablegung Christi, for five solo voices, 2 mixed choirs and orchestra (1969), 50 mn, Schott

- Kosmogonia for soloists, mixed choir and orchestra (1970), 20 mn, Schott

- Utrenja II Auferstehung, for soloists, children's choir, two mixed choirs and orchestra (1970-1971), 36 mn, Schott

- Canticum Canticorum Salomonis for mixed 16-part choir, chamber orchestra and a couple of dancers ad lib. (1970-1973), 17 mn, Schott

- Magnificat for solo bass, vocal ensemble, 2 mixed choirs, children's voices and orchestra (1973), 40 mn, Schott

- elec stage Paradise Lost Sacra Rappresentazione, in two acts (1976-1978), 3 h, Schott

- stage Vorspiel, Visionen und Finale from Paradise Lost, for 6 soloists, large mixed choir and orchestra (1979), 40 mn, Schott

- Lacrimosa from the Polnischen Requiem, for solo soprano, mixed choir and orchestra (1980), 6 mn, Schott

- Te Deum for 4 solo voices, 2 mixed choirs and orchestra (1979-1980), 35 mn, Schott

- Polnisches Requiem for four solo voices, mixed choir and orchestra (2005, 1980-1984, 1993), 1 h 48 mn, Schott

- stage Die schwarze Maske one act opera (1984-1986), 1 h 40 mn, Schott

- Zwei Szenen und Finale from the opera Die schwarze Maske for soprano, mezzo-soprano, mixed choir and orchestra (1988), 30 mn, Schott

- stage Ubu Rex Opera buffa in two acts (1990-1991), 2 h, Schott

- Sanctus from the Polnischen Requiem, for contralto and tenor, mixed choir and orchestra (1993-1994), 15 mn, Schott

- Agnus Dei from the Requiem der Versöhnung, for four solo voices, mixed choir and orchestra (1995), 6 mn, Schott

- Seven Gates of Jerusalem - Sinfonie n° 7 for 5 solo voices, narrator, 3 mixed choirs and orchestra (1996), 1 h 8 mn, Schott

- Hymne an den heiligen Adalbert for mixed choir and ensemble (1997), 5 mn, Schott

- Hymne an den heiligen Daniel Slawa swjatamu dlinnju knazju moskowskamu, for mixed choir and orchestra (1997), 14 mn, Schott

- Credo for 5 solo voices, children's choir, mixed choir and orchestra (1997-1998), 60 mn, Schott

- stage Suite from Paradise Lost, for soloists, choir and orchestra (2000), 1 h 40 mn, Schott

- Sinfonie n° 8 - Lieder der Vergänglichkeit for three solo voices, mixed choir and orchestra (2005, 2007), 55 mn, Schott

- Kadisz for soprano, tenor, narrator, male choir and orchestra (2009), 20 mn, Schott

- "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott" for mixed choir, brass instruments, percussions and string orchestra (2010), 5 mn, Schott

- "Powiało na mnie morze snów..." reflective and nostalgic lieder for soprano, mezzo-soprano, baritone, mixed choir and orchestra (2010), 60 mn, Schott

- "Powiało na mnie morze snów..." reflective and nostalgic lieder for soprano, mezzo-soprano, baritone, mixed choir and orchestra (2010), 60 mn

- Dies illa for three solo voices, three mixed choirs and orchestra (2014), 22 mn, Schott

- 6. Sinfonie Chinese songs for baritone and orchestra (2008-2017), 25 mn, Schott

- Lacrimosa no. 2 for soprano, women's choir and chamber orchestra (2018), 2 mn, Schott

- A cappella vocal music

- Stabat Mater from Passio and bit Domini nostri Jesu Christi secundum Lucam, for three mixed choirs a cappella /i> (1962), 8 mn, Schott

- In Pulverem Mortis from Passio et mors Domini nostri Jesu Christi secundum Lucam, for three mixed choirs a cappella (1965), 7 mn, Schott

- Miserere taken from Passio et mors Domini nostri Jesu Christi secundum Lucam, for children's choir ad lib and three mixed choirs a cappella (1965), 4 mn, Schott

- Ecloga VIII Vergili Bucolica, for six male voices a cappella (1972), 9 mn, Schott

- Agnus Dei from the Polnischen Requiem, for mixed choir a cappella (1981), 8 mn, Schott

- Ize cheruvimi for mixed choir a cappella (1986-1987), 8 mn, Schott

- Veni creator for mixed choir a cappella (1987), 8 mn, Schott

- Benedicamus Domino Organum und Psalm 117, for male choir a cappella (1992), 4 mn, Schott

- Benedictus for mixed choir a cappella (1993), 10 mn, Inédit

- De profundis Psalm 129, 1-3, taken from Seven Gates of Jerusalem, for three mixed choirs a cappella (1996), 8 mn, Schott

- Iz glubiny (psalm 130), from Seven Gates of Jerusalem, for three mixed choirs a cappella (1996, 2013), 4 mn, Schott

- Sanctus und Benedictus for children's choir a cappella (2008, 2002), 6 mn, Schott

- Kaczka pstra Polish lullaby for 2 female or children's choirs (2009), 2 mn, Schott

- O gloriosa virginum for mixed choir a cappella (2009), 5 mn, Schott

- Prosimy cie from Kadisz, for a cappella male choir (2009), 2 mn, Schott

- Grób Potockiej from Powiało na mnie morze snów ..., for mixed a cappella choir (2010), 2 mn, Schott

- Missa brevis for mixed choir (2012), 20 mn, Schott

- Quid sum miser from Dies illa, for three mixed a cappella choirs (2014), 3 mn, Schott

- Recordare from Dies illa, for mixed a cappella choir (2014), 2 mn, Schott

- Domine quid multiplicati sunt psalm 3, for mixed choir a cappella (2015), 7 mn, Schott

- My też pastuszkowie Polish song for mixed choir (2015), 2 mn, Schott

- Electronic music / fixed media / mechanical musical instruments

- Psalmus for magnetic tape (1961), 5 mn, Schott

- stage Brygada śmierci opera for narrator and tape (1963), 30 mn, Schott

- elec Aulodija for tape (1972), 3 mn, Inédit

- Ekechejria for magnetic tape (1972), between 2 mn 50 s and 3 mn 25 s, Inédit

- Unspecified instrumentation

- Concerto doppio for violin, viola and orchestra (2012), 22 mn, Schott

- 2018

- Fanfare for the independent Poland for seven brass instruments, timpani and percussion, 60 s, Schott

- Lacrimosa no. 2 for soprano, women's choir and chamber orchestra, 2 mn, Schott

- Polonaise for orchestra, 2 mn, Schott

- 2017

- 6. Sinfonie Chinese songs for baritone and orchestra, 25 mn, Schott

- Concerto for accordion and orchestra, 22 mn, Schott

- Concerto doppio version for flute, clarinet and orchestra, 22 mn, Schott

- 2016

- Quartetto per archi no. 4, 15 mn, Schott

- Tanz viola version, 2 mn, Schott

- 2015

- Ciaccona In memoriam Giovanni Paolo II, transcription for six cellos, 7 mn, Schott

- Concertino for trumpet and orchestra, 12 mn, Schott

- Domine quid multiplicati sunt psalm 3, for mixed choir a cappella, 7 mn, Schott

- My też pastuszkowie Polish song for mixed choir, 2 mn, Schott

- Polonaise for orchestra, 7 mn, Schott

- 2014

- Dies illa for three solo voices, three mixed choirs and orchestra, 22 mn, Schott

- Quid sum miser from Dies illa, for three mixed a cappella choirs, 3 mn, Schott

- Recordare from Dies illa, for mixed a cappella choir, 2 mn, Schott

- 2013

- Adagio from Sinfonie n° 3 for orchestra, 14 mn, Schott

- Adagio from Symphony No.3 for string orchestra, 14 mn, Schott

- La Follia for violin, 13 mn, Schott

- Quintetto per archi for string quintet, after String Quartet No.3, 15 mn, Schott

- Suite for cello, 20 mn, Schott

- Tempo di valse for viola, 3 mn, Schott

- 2012

- Capriccio per Radovan "Il sogno di un cacciatore", for horn, 4 mn, Schott

- Concerto doppio for violin, viola and orchestra, 22 mn, Schott

- De natura sonoris n° 3 for orchestra, 7 mn, Schott

- Missa brevis for mixed choir, 20 mn, Schott

- Sinfonietta n° 3 for string quartet, 15 mn, Schott

- 2011

- Violoncello totale for cello, 6 mn, Schott

- 2010

- "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott" for mixed choir, brass instruments, percussions and string orchestra, 5 mn, Schott

- "Powiało na mnie morze snów..." reflective and nostalgic lieder for soprano, mezzo-soprano, baritone, mixed choir and orchestra, 60 mn, Schott

- "Powiało na mnie morze snów..." reflective and nostalgic lieder for soprano, mezzo-soprano, baritone, mixed choir and orchestra, 60 mn

- Duo concertante for violin and double bass, 6 mn 10 s, Schott

- Grób Potockiej from Powiało na mnie morze snów ..., for mixed a cappella choir, 2 mn, Schott

- Tanz for viola, 2 mn, Schott

- 2009

- Ciaccona In memoria Giovanni Paolo II, for violin and viola (or cello), 7 mn, Schott

- Kaczka pstra Polish lullaby for 2 female or children's choirs , 2 mn, Schott

- Kadisz for soprano, tenor, narrator, male choir and orchestra, 20 mn, Schott

- O gloriosa virginum for mixed choir a cappella, 5 mn, Schott

- Prelude for Peace for brass, timpani and percussion, 4 mn, Schott

- Prosimy cie from Kadisz, for a cappella male choir, 2 mn, Schott

- Tanz for violin, 2 mn, Schott

- 2008

- Capriccio for solo violin, 3 mn, Schott

- Concerto Winterreise, for horn and orchestra, 16 mn, Schott

- Danziger Fanfare for brass, timpani and percussion, 2 mn, Schott

- Quartetto per archi n° 3, Schott

- Sinfonietta n° 3 leaves from an unwritten diary, version for string orchestra, 15 mn, Schott

- 2007

- 2006

- Kadenz for the Brandenburg Concerto in G major by Johann Sebastian Bach, for viola, cello and harpsichord, 2 mn, Schott

- 2005

- Ciaccona In memoria Giovanni Paolo II, for string orchestra, 12 mn, Schott

- Ciaccona from Polnisches Requiem, In memoria Giovanni Paolo II, for string orchestra, 7 mn, Schott

- Sinfonie n° 8 - Lieder der Vergänglichkeit for three solo voices, mixed choir and orchestra, 55 mn, Schott

- 2004

- Concerto grosso n° 2 for five clarinets and orchestra, 17 mn, Schott

- 2003

- Fanfarria Real for orchestra, 5 mn, Schott

- Largo for cello and orchestra, 28 mn, Schott

- 2002

- Sanctus und Benedictus for children's choir a cappella, 6 mn, Schott

- 2001

- Concerto Resurrection, for piano and orchestra, 38 mn, Schott

- Concerto Grosso for three cellos and orchestra, 35 mn, Schott

- 2000

- 1999

- Kadenzen for the concerto for trumpet and orchestra by Joseph Haydn in Eb major, for solo trumpet with accompaniment of two horns, 4 mn, Schott

- Sonata n° 2 for violin and piano, 35 mn, Schott

- 1998

- Credo for 5 solo voices, children's choir, mixed choir and orchestra, 60 mn, Schott

- De profundis from Seven Gates of Jerusalem, version for string orchestra, 7 mn, Schott

- Luzerner Fanfare for 8 trumpets and percussion, 6 mn, Schott

- 1997

- Hymne an den heiligen Adalbert for mixed choir and ensemble, 5 mn, Schott

- Hymne an den heiligen Daniel Slawa swjatamu dlinnju knazju moskowskamu, for mixed choir and orchestra, 14 mn, Schott

- Serenade für Streichorchester, 10 mn, Schott

- 1996

- De profundis Psalm 129, 1-3, taken from Seven Gates of Jerusalem, for three mixed choirs a cappella, 8 mn, Schott

- Iz glubiny (psalm 130), from Seven Gates of Jerusalem, for three mixed choirs a cappella, 4 mn, Schott

- Seven Gates of Jerusalem - Sinfonie n° 7 for 5 solo voices, narrator, 3 mixed choirs and orchestra, 1 h 8 mn, Schott

- 1995

- Agnus Dei from the Requiem der Versöhnung, for four solo voices, mixed choir and orchestra, 6 mn, Schott

- Burleske Suite aus Ubu Rex for large wind orchestra, establishment by Henning Brauel, 16 mn, Schott

- Metamorphosen Concerto for violin and orchestra n° 2, 35 mn, Schott

- Sinfonie n° 3 for orchestra, 50 mn, Schott

- 1994

- Divertimento for solo cello, 17 mn, Schott

- Entrata for brass and timpani, 4 mn, Schott

- Musik aus «Ubu Rex» for orchestra, establishment by Henning Brauel, 25 mn, Schott

- Sanctus from the Polnischen Requiem, for contralto and tenor, mixed choir and orchestra, 15 mn, Schott

- Sinfonietta n° 2 for clarinet and strings, 20 mn, Schott

- 1993

- Benedictus for mixed choir a cappella, 10 mn, Inédit

- Concerto for flute (or clarinet: 1995 version) and chamber orchestra, 25 mn, Schott

- Quartett for clarinet and string trio, 20 mn, Schott

- 1992

- Benedicamus Domino Organum und Psalm 117, for male choir a cappella, 4 mn, Schott

- Sinfonie n° 5 "Coréenne", for orchestra, 35 mn, Schott

- 1991

- Sinfonietta per archi for string orchestra, 12 mn, Schott

- stage Ubu Rex Opera buffa in two acts, 2 h, Schott

- 1990

- Streichtrio for violin, viola and cello, 12 mn, Schott

- 1989

- Adagio Sinfonie n° 4 for large orchestra, 33 mn, Schott

- 1988

- Der unterbrochene Gedanke for string quartet, 3 mn, Schott

- Zwei Szenen und Finale from the opera Die schwarze Maske for soprano, mezzo-soprano, mixed choir and orchestra, 30 mn, Schott

- 1987

- Ize cheruvimi for mixed choir a cappella, 8 mn, Schott

- Prélude for clarinet in Bb solo, 2 mn, Schott

- Veni creator for mixed choir a cappella, 8 mn, Schott

- 1986

- stage Die schwarze Maske one act opera, 1 h 40 mn, Schott

- Per Slava for solo cello, 6 mn, Schott

- 1984

- Cadenza version for solo viola by Christiane Edinger, 8 mn, Schott

- Cadenza for solo viola, 8 mn, Schott

- Concerto for viola (or cello or clarinet), version for chamber orchestra, strings, percussion and celesta, 22 mn, Schott

- Polnisches Requiem for four solo voices, mixed choir and orchestra, 1 h 48 mn, Schott

- 1983

- Concerto for viola (or cello or clarinet) and orchestra, 22 mn, Schott

- 1982

- Concerto for cello and orchestra n° 2, 35 mn, Schott

- 1981

- Agnus Dei from the Polnischen Requiem, for mixed choir a cappella, 8 mn, Schott

- 1980

- Capriccio for solo tuba, 6 mn, Schott

- Lacrimosa from the Polnischen Requiem, for solo soprano, mixed choir and orchestra, 6 mn, Schott

- Sinfonie n° 2 "Christmas Symphony" for orchestra, 36 mn, Schott

- Te Deum for 4 solo voices, 2 mixed choirs and orchestra, 35 mn, Schott

- 1979

- Adagietto from Paradise Lost for orchestra, 5 mn, Schott

- stage Vorspiel, Visionen und Finale from Paradise Lost, for 6 soloists, large mixed choir and orchestra, 40 mn, Schott

- 1978

- elec stage Paradise Lost Sacra Rappresentazione, in two acts, 3 h, Schott

- 1977

- Concerto for violin and orchestra, 40 mn, Schott

- 1974

- Przebudzenie Jakuba for symphony orchestra, between 8 mn and 12 mn, Schott

- 1973

- Canticum Canticorum Salomonis for mixed 16-part choir, chamber orchestra and a couple of dancers ad lib., 17 mn, Schott

- Intermezzo for 24 stringed instruments, 7 mn, Schott

- Magnificat for solo bass, vocal ensemble, 2 mixed choirs, children's voices and orchestra, 40 mn, Schott

- Sinfonie n° 1 for orchestra, 30 mn, Schott

- 1972

- elec Aulodija for tape, 3 mn, Inédit

- Ecloga VIII Vergili Bucolica, for six male voices a cappella, 9 mn, Schott

- Ekechejria for magnetic tape, between 2 mn 50 s and 3 mn 25 s, Inédit

- 1971

- Actions for jazz ensemble, 17 mn, Schott

- De natura sonoris n° 2 for orchestra, 10 mn, Schott

- Partita for harpsichord, electric guitar, bass, harp, double bass and orchestra, 19 mn, Schott

- Preludium for wind, percussion and double bass orchestra, 8 mn, pas d'éditeur

- Utrenja II Auferstehung, for soloists, children's choir, two mixed choirs and orchestra, 36 mn, Schott

- 1970

- Kosmogonia for soloists, mixed choir and orchestra, 20 mn, Schott

- 1969

- Die Teufel von Loudun opera in three acts, 1 h 50 mn, Schott

- Utrenja I Grablegung Christi, for five solo voices, 2 mixed choirs and orchestra, 50 mn, Schott

- 1968

- Capriccio per Siegfried Palm for solo cello, 6 mn, Schott

- Quartetto per archi n° 2, 7 mn 30 s, Schott [program note]

- 1967

- Capriccio for violin and orchestra, 10 mn, Schott

- Concerto for cello and orchestra, 20 mn, Schott

- Dies Irae Oratorium ob memoriam in perniciei castris in Oswiecim necatorum inexstinguibilem reddendam, for soprano, tenor, bass, mixed choir and orchestra, 22 mn, Schott

- Uwertura pittsburska for wind orchestra, percussion and keyboards, variable, Peters

- 1966

- De natura sonoris n° 1 for orchestra, 8 mn, Schott

- Passio Et Mors Domini Nostri Jesu Christi Secundum Lucam for soprano, baritone, bass, narrator, children's choir, two mixed choirs and orchestra, 1 h 20 mn, Schott

- 1965

- In Pulverem Mortis from Passio et mors Domini nostri Jesu Christi secundum Lucam, for three mixed choirs a cappella, 7 mn, Schott

- Miserere taken from Passio et mors Domini nostri Jesu Christi secundum Lucam, for children's choir ad lib and three mixed choirs a cappella, 4 mn, Schott

- stage Najdzielniejzy z rycerzy Children's opera in three acts, 60 mn, Inédit

- 1964

- Cantata in honorem Almae Matris Universitatis Iagellonicae sescentos abhinc annos fundatae for two mixed choirs and orchestra, 6 mn, Schott

- Capriccio for oboe and 11 string instruments, 7 mn, Schott

- Sonata for cello and orchestra, 10 mn, Schott

- 1963

- stage Brygada śmierci opera for narrator and tape, 30 mn, Schott

- Drei Stücke im alten Stil based on the music for the film Die Handschrift von Saragossa, for string orchestra, 6 mn, Schott

- 1962

- Aria [et] Deux menuets for string orchestra, 3 mn 35 s, Schott

- Fluorescences for orchestra, 16 mn, Schott

- elec Kanon for string orchestra and magnetic tape, 10 mn, Schott

- Stabat Mater from Passio and bit Domini nostri Jesu Christi secundum Lucam, for three mixed choirs a cappella /i>, 8 mn, Schott

- 1961

- Fonogrammi for flute and chamber orchestra, 7 mn, Schott

- Polymorphia for 48 string instruments, 10 mn, Schott

- Psalmus for magnetic tape, 5 mn, Schott

- 1960

- Anaklasis for strings and percussion, 9 mn, Schott

- Dimensionen der Zeit und der Stille for mixed choir of 40 voices and percussion and string ensemble, 15 mn, Schott

- Quartetto per archi n°1, 8 mn, PWM (Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne)

- Threnos Den Opfern von Hiroshima, for 52 string instruments, 8 mn, Schott

- 1959

- Emanationen for two string orchestras, 8 mn, Schott

- Miniatures for violin and piano, variable, PWM (Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne)

- Strophen for soprano, spoken voice and ensemble, 8 mn, Schott

- 1958

- Aus den Psalmen Davids for mixed choir and ensemble, 10 mn, Schott

- Epitafium Artur Malawski in memoriam for strings and timpani, 4 mn, Schott

- 1956

- Tre miniature for clarinet and piano, 3 mn, Schott

- 1953

- Sonate for violin and piano, 9 mn, Schott

Bibliographie sélective

- Regina CHLOPICKA, « Les liens entre la musique de Penderecki et la tradition de ritualité religieuse », dans Les cahiers du CIREM n° 44-45-46, éd. Centre International de Recherches en Esthétique Musicale, décembre 1999.

- Regina CHLOPICKA, Krzysztof Penderecki : musica sacra - musica profana : a study of vocal-instrumental works, Varsovie, Adam Mickiewicz Institut, 2003.

- Barbara MALECKA-CONTAMIN, Krzysztof Penderecki. Style et matériaux, Paris, Kimé, 1997.

- Danuta MIRKA, The sonoristic structuralism of Krzysztof Penderecki, Katowice, Music Academy, 1997.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Le Labyrinthe du temps. Cinq leçons pour une fin de siècle, traduit du polonais par François Rosset, éditions Noir sur Blanc, Montricher (Suisse), 1998.

- Wolfram SCHWINGER, Krzysztof Penderecki. His life and work, Londres, Schott, 1979.

- Mieczysław TOMASZEWSKI, Penderecki,Intitut Adam Mickiewicz, 2003.

Cds, Dvds

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, La Follia ; Sonata n° 2 ; Metamorphosen, Anne-Sophie Mutter : violon, The London Symphony Orchestra, dans « Hommage à Penderecki », 2 CD Deutsche Grammophon, 2018, 483 5163 GH2.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Stabat Mater, Pasja ; Ut Quid ; Miserere ; In Pulverem Mortis ; Veni Creator ; Będę Cię Wielibił, Panie ; Pieśń Cherubinów ; Quid Sum Miser (Dies Illa) ; Recordare (Dies Illa) ; O Gloriosa Virginum ; Kaczka Pstra ; Missa Brevis ; Sicut Locutus Est ; Prosimy Cie ; Agnus Dei (Polskie Requiem) ; Benedictum Dominum ; De Profundis (Siedem Bram Jerozolimy) ; Grob Potockiej (Powialo Na Mnie Moze Slow…) ; Aria (Trzy Utwory W Dawnym Stylu), Filharmonia Narodowa, dans « Penderecki conducts Penderecki, vol. 2 », 2 CD Warner Classics, 2017, 01902 9 58195 5 2.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Dies illa ; Hymn to St. Danill ; Hymn to St. Adalbert ; Psalms of David, Filharmonia Narodowa, dans « Penderecki conducts Penderecki, vol. 1 », 1 CD Warner Classics, 2016, 08256 4 60393 9 5.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, « A Tribute to Krzysztof Penderecki », Threnos ; Duo concertante ; Concerto grosso per tre violoncelli ed orchestra ; Credo, Anne-Sophie Mutter : violon, Daniel Müller-Schott : violoncelle, Sinfonia Varsovia, direction : Charles Dutoit, Valery Gergiev, Krzysztof Urbanski, 1 DVD ACCENTUS MUSIC ACC 20276, 2014.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, « Complete Symphonies », Polish Sinfonia Iuventus Orchestra, direction : Krzysztof Penderecki, 1 Cd DUX 0947, 2013.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, « Resurrection », Concerto per pianoforte ed orchestra, Florian Uhlig : piano, Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, direction : Łukasz Borowicz, 1 Cd HÄNSSLER CLASSIC 98.018, 2013.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Sinfonie n°8, Iwona Hossa : soprano, Agnieszka Rehlis : alto, Thomas E. Bauer : baryton, Chor der Podlachischen Oper und Philharmonie in Białystok, Orchester Polnische Sinfonia Iuventus, direction : Krzysztof Penderecki, 1 Cd DUX 0901, 2013.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Serenade ; Sinfonietta n°2 (versione per flauto ed archi) ; Sinfonietta per archi ; Concerto per viola (violoncello/clarinetto) ed archi, percussione e celesta, Łukasz Długosz : flûte, Rafał Kwiatkowski : violoncelle, Radom Chamber Orchestra, direction : Maciej Żółtowski, 1 Cd DUX 0935, 2013.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Concerto per pianoforte ed orchestra ; Concerto per flauto (clarinetto) ed orchestra da camera, Barry Douglas : piano, Lukasz Dlugosz : flûte, Orchestre Philharmonique de Varsovie, direction : Antoni Wit, 1 Cd NAXOS 8.572696, 2013.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, « Complete Symphonies », Michaela Kaune : soprano, Agnieszka Rehlis : mezzo-soprano, Anna Lubanska : mezzo-soprano, Ryszard Minkiewicz : ténor, Wojtek Drabowicz : baryton, Jaroslaw Brek : baryton-basse, Chœur et Orchestre Philharmonique de Varsovie, Orchestre symphonique national de la radio polonaise, direction : Antoni Wit, 1 Cd NAXOS 8.505231, 2012.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Hymne an den heiligen Adalbert ; Cherubinischer Lobgesang - Iže cheruvimi ; Canticum Canticorum Salomonis ; Kosmogonia, Olga Pasichnyk : soprano, Rafal Bartminski : ténor, Tomasz Konieczny : basse, Jerzy Artysz : récitant, Chœur et Orchestre Philharmonique de Varsovie, direction : Antoni Wit, 1 Cd NAXOS 8.572481, 2012.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Fonogrammi ; Als Jakob erwachte ; Anaklasis ; De natura sonoris n°1 ; Partita Concerto per corno ed orchestra, Urszula Janik : flûte, Elzbieta Stefanska : clavecin, Jennifer Montone : cor, Orchestre Philharmonique de Varsovie, direction : Antoni Wit, 1 Cd NAXOS 8.572482, 2012.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Drei Stücke im alten Stil ; Sinfonietta per archi ; Sinfonietta no. 2 ; Serenade Intermezzo ; Capriccio per oboe ed 11 archi, Jean-Louis Capezzali : hautbois, Artur Pachlewski : clarinette, Orchestre de Chambre Philharmonique de Varsovie, direction : Antoni Wit, 1 Cd NAXOS 8.572212, 2012.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Powiało na mnie morze snów…, Wioletta Chodowicz : soprano, Agnieszka Rehlis : mezzo-soprano, Mariusz Godlewski : baryton, Chór Filharmonii Narodowej, Sinfonia Varsovia, direction : Valery Gergiev, 1 Cd NARODOWY INSTYTUT FRYDERYKA CHOPINA NIFCCD 30, 2011.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Concerto pour alto, cordes, percussions et célesta ; Concerto n°2 pour violoncelle, Grigorij Zhyslin : alto, Tatjana Vassilieva : violoncelle, Orchestre Philharmonique de Varsovie, direction : Antoni Wit, 1 Cd NAXOS 8.572211, 2011.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Concerto pour alto et orchestre ; Concerto pour violoncelle et orchestre n°2, Grigorij Zhyslin : alto, Tatjana Vassilieva : violoncelle, Orchestre Philharmonique de Varsovie, direction : Antoni Wit, 1 Cd NAXOS 8.572211, 2011.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Credo ; Cantata in honorem Almae Matris Universitatis Iagellonicae sescentos abhinc annos fundatae, Iwona Hossa, Aga Mikolaj : sopranes, Ewa Wolak : alto, Rafal Bartminski : ténor, Remigiusz Lukomski : basse, Chœur d’hommes de Varsovie, Chœur et Orchestre Philharmonique de Varsovie, direction : Antoni Wit, 1 Cd NAXOS 8.572032, 2011.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Adagietto ; Ciaccona ; Agnus Dei ; Intermezzo ; De profundis ; Serenade ; Drei Stücke im alten Stil ; Sinfonietta per archi, Albrecht Mayer : cor anglais, Jakub Haufa : violon, Artur Paciorkiewicz : alto, Jerzy Klocek : violoncelle, Sinfonia Varsovia, direction : Krzystof Penderecki, 1 Cd DUX 0678, 2009.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Utrenja I ; Utrenja II, Hossa Iwona : soprano, Agnieszka Rehlis : mezzo-soprano, Piotr Kusiewicz : ténor, Genady Bezzubenkov : basse, Piotr Nowacki : basse, Chœur et Orchestre Philharmonique de Varsovie, direction : Antoni Wit, 1 Cd NAXOS 74731320317, 2009.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Seven Gates of Jerusalem - Sinfonie n°7, solistes, chœur et orchestre de l’Académie de Musique de Cracovie, direction : Krzysztof Penderecki, 1 Cd DUX 0546, 2009.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, « Works for Cellos and Orchestra » , Concerto grosso ; Largo ; Sonata, Warsaw National Philharmonic Orchestra, Rafal Kwiatkowski, Ivan Monighetti, Arto Noras : violoncelles, Antoni Wit : direction, 1 Cd Naxos n° 8.570509, 2008.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Symphony No. 8 ; Dies irae ; Aus den Psalmen Davids, Michaela Kaune : soprano, Agnieszka Rehlis et Anna Lubanska : mezzo-sopranos, Ryszard Minkiewicz : ténor, Wojtek Drabowicz : baryton, Jaroslaw Brek : baryton-basse, chœur et orchestre philharmonique de Varsovie, Antoni Wit : direction, 1 Cd Naxos n° 8.570450, 2008.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Capriccio ; De natura sonoris Nr. 2 ; Resurrection, Patrycja Piekutowska : violon, Beata Bilinska : piano, National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra Katowice, direction : Krzysztof Penderecki, 1 Cd DUX n°0582, 2007.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Te Deum ; Hymne an den Heiligen Daniel ; Polymorphia ; Ciaconna, Izabela Klosinska : soprano, Piotr Nowacki : basse, Agnieszka Rehlis : mezzo-soprano, Adam Zdunikowski : ténor, chœur philharmonique de Varsovie, 1 Cd Naxos 8.557980, 2007.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Die Teufel von Loudun, Tatiana Troyanos, Andrzej Hiolski, Bernard Ladysz, Hans Sotin, Karl-Heinz Gerdesmann, Rolf Mamero, Kurt Marschner, Heinz Blankenburg, Philharmonisches Staatsorchester Hamburg, Marek Janowski : direction, Historical Studio Production from the Hamburger Staatsoper, 1969, 1 Dvd ARTHAUS, n° 101 279, 2007.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Concerto pour violoncelle et orchestre n° 2, dans« Beethoven Orchester Bonn » avec la Symphonie n° 7 en la majeur op. 92 de Beethoven, 1 Cd Schott Music, enregistrement du Internationalen Beethovenfestes Bonn 2002.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Les diables de Loudun, Tatiana Troyanos : Jeanne, Kndrzej Hiolsky : Urbain Grandier, Bernard Ladvsz : Vater Barré, Hans Sotin : Vater Rangier, Horst Wilhelm : Vater Mignon, Kurt Marschner : Adam, Heinz Blankenburg : Mannoury, Helmut Melchert : Baron de Laubardemont, Opéra National d’Hamburg, Marek Janowski : direction, 1 Cd Philips (enregistré en 1969), n° 446 32.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Polish Requiem ; Die Irae ; Requiem, Jadwiga Gadulanka : soprano, Jadwiga Rappe : alto, Henryk Grychnik : ténor, Carlo Zardo : basse, chœur de la radio polonaise de Cracovie, chœur philharmonique de Cracovie, orchestre national symphonique de la radio polonaise de Cracovie, Antoni Wit : direction, Dies Irae : Stefania Woytowicz : soprano, Wieslaw Ochman : ténor, Bernard Ladysz : basse, chœur philharmonique de Cracovie, chœur et orchestre philharmonique de Cracovie, Henryk Czyz : direction, Polskie Nagrania, 1 Cd PNCD, n° 021 A (AAD), 1989.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Konzert für Viola und Kammerorchester, Tabea Zimmermann, Amadeus Kammerorchester Posen, direction : Agnieszka Duczmal, 1 Cd Wergo, n° WER 60172-50.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Don CHERRY, Actions, Don Cherry, Mocqui Cherry, Loes MacGillycutty, 1 Cd Intuition, INT 36062.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, « Musica da camera », comprenant : Quartetto per archi n° 1 ; Quartetto per archi n° 2 ; Streichtrio ; Der unterbrochene Gedanke für Streichquartett ; Sonate für Violine und Klavier ; Miniatury. Drei Miniaturen für Violine und Klavier ; 3 miniature per clarinetto e pianoforte ; Cadenza per viola sola ; Per Slava für Violoncello solo ; Capriccio per Siegfried Palm für Violoncello solo ; Prelude for Solo Clarinet in B flat, Szábolcs Esztényi, Konstanty Andrzej Kulka, Waldemar Malicki, Ivan Monighetti, Artur Paciorkiewicz, Aleksander Romanski, 1 Cd Wergo, WER 62582.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, « Per coro », comprenant Aus den Psalmen Davids ; Stabat Mater und Psalmen ; Sicut locutus est ; Agnus Dei ; Song of Cherubim ; Veni creator spiritus, chœur et solistes de l’orchestre national philharmonique de Varsovie, direction : Krzysztof Penderecki, 1 Cd Wergo, WER 62612.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, 2. Sinfonie / Adagio (4. Sinfonie), NDR Sinfonieorchester, direction Krzysztof Penderecki, 1 Cd Wergo, WER 62702.

- Krzysztof PENDERECKI, Seven Gates of Jerusalem, Bozena Harasimowicz-Haas, Izabella Klosinska, Wieslaw Ochman, Jadwiga Rappé, Romuald Tesarowicz, Henryk Wojnarowski, National Philharmonic Choir Warsaw, direction : Kazimierz Kord, 1 Cd Wergo, WER 66472.

Sites Internet

- Schott : http://www.penderecki.de

- Culture polonaise : http://www.culture.pl/fr/culture/artykuly/os_penderecki_krzysztof

- Klassika : informations sur Penderecki, en allemand : http://www.klassika.info/Komponisten/Penderecki_Krzysztof/index.html

(liens vérifiés en mars 2020).