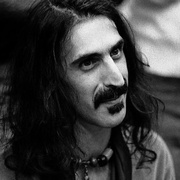

Frank Zappa

American composer and multi-instrumentalist, born 21 December 1940 in Baltimore, died 4 December 1993 in Los Angeles.

Largely self-taught, at around the age of 12, Zappa became interested in drumming. In 1953, he attended a Summer course where he learnt the basics of playing the drumkit. In 1954, he composed his first piece, of which no trace remains. His second work, Mice, for solo snare drum, was composed soon thereafter, the score of which is housed in the composer’s archives.

At around the age of 14, Zappa became familiar with the music of Edgard Varèse and, thanks to a teacher at the Mission Bay High School in San Diego, with serial music. At age 15, he joined the R&B group The Ramblers as the drummer, and performed in his first concerts. He was also the drummer of the group The Blackouts in 1957-58. At around this time, Zappa became fascinated with the guitar solos that featured in R&B music, avidly collecting recordings of artists such as Johnny “Guitar” Watson and Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, among others, and took up the instrument himself.

In 1958, Zappa conducted the Antelope Valley Junior College Orechstra in some performances of his own works. In 1959, an English teacher that he had met three years earlier at Antelope Valley High School, Don Cerveris, asked Zappa to compose an orchestral score for the film Run Home, Slow (the film, directed by Tim Sullivan, a.k.a. Ted Brenner, was not released until December 1965). After graduating from secondary school, Zappa undertook studies in music in any way that he could, e.g., attending a Summer course at the Idyllwild Art & Music School in 1958, a few weeks of music theory lessons at Chaffey Junior College in Alta Loma (1960), and composition classes with Karl Kohn at Pomona College in Claremont (1961).

In addition to his talent as a musician, Zappa excelled in visual arts, winning a poster design competition in 1955 and a California statewide competition in 1958. In 1960, he worked designing greeting cards and advertisments. That same year, he met Paul Buff, a sound engineer that had built his own studio, the Pal Recording Studio. As a multi-instrumentalist himself, Buff hired Zappa as his assistant and as an in-house musician and composer, with the goal of producing hit surf music records. This enterprise saw little success, and Buff ultimately ceded control of his studio to Zappa, who was able to fund the transaction after having finally received payment for his work on Run Home, Slow. On 1 August 1964, the studio was renamed Studio Z.

In the beginning of the 1960s, Zappa worked with various groups as a guitarist, while simultaneously establishing himself as an experimental composer. In March 1963, he appeared on the The Steve Allen Show to perform his Concerto for two bicycles, pre-recorded sounds and ensemble with the studio orchestra. In May of that year, Zappa conceived a concert programme titled “The Experimental Music of Frank Zappa,” which he proposed to Mount St. Mary’s College in Los Angeles. In 1964, he developed the concept of the rock opera through the composition of I Was A Teen-age Malt Shop (he returned to this genre with Joe’s Garage in 1979 and Thing Fish in 1984), and wrote his first film script, Captain Beefheart vs. The Grunt People. Over the course of his career, Zappa wrote, produced, and directed several films, such as 200 Motels (1971), Baby Snakes (1979), Video From Hell (1987), etc.

In May 1965, the rock group led by Zappa changed its name to “The Mothers” (as the name was considered offensive by some, it was appended with “of Invention” before the release of the album Freak Out! in 1966). Although The Mothers of Invention, which transformed into an “electric chambre ensemble,” disbanded in 1969, Zappa would lead professional ensembles and perform his own compositions throughout his career. His music came to be characterised as a mixture of popular and highbrow styles, with lyrics severely critical of American politics and the “American way of life”, and with a distinct sense of humour that often bordered on vulgarity. Despite a preference for working with large ensembles and instrumental music, Zappa deftly adapted to financial constraints which forced him to tour with small groups (e.g., his “rockin’ teenage combo”) and to compose “songs.”

Zappa has been cited as an influence by a number of musicians working in various genres (rock, jazz, concert music, etc.) who seek to transgress musical boundaries. His peers who have had the acumen to look beyond the image of the “vulgar clown”, as he was portrayed by the media, have discovered a composer that was worthy of attention. For example, Pierre Boulez agreed to collaborate with Zappa on the performance and recording of several of the latter’s works (Boulez Conducts Zappa: The Perfect Stranger, Angel, 1984). Recognition from Boulez opened the eyes of many to the merits of Zappa’s work. For example, while at IRCAM, Kent Nagano learnt that there was to be a collaboration between Boulez and Zappa, and as such, that Zappa also composed “serious” music. The subsequent correspondence between Zappa and Nagano culminated in the premieres of several of Zappa’s works with the London Symphony Orchestra and the release of the first record of the LSO under Nagano’s direction, London Symphony Orchestra Vol. 1, Barking Pumpkin, in 1983.

Zappa toured the world as a rock performer for the last time in 1988 with a group comprising some twelve musicians. His final performance took place in September 1992, when he conducted the Ensemble Modern in Frankfurt. On 4 December 1993, he died of prostate cancer. His discography, which is managed by the Zappa Family Trust and which already comprises some 60 titles, continues to grow through the release of archival and bootleg material.

Sources

- Kelly FISHER LOWE, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, Westport, Praeger, The Praeger Singer-Songwriter Collection, 2006.

- Román GARCIA ALBERTOS*, Information Is Not Knowledge*, http://globalia.net/donlope/fz, vérifié le 19 novembre 2012.

- Barry MILES, Frank Zappa In His Own Words, Londres, Omnibus Press, 1993.

- David WALLEY, No Commercial Potential - The Saga of Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention, New York, Outerbridge & Lazard, 1972.

- Frank ZAPPA et Peter OCCHIOGROSSO, The Real Frank Zappa Book, New York, Poseidon Press, 1989.

By Réjean Beaucage

Frank Zappa is one of the most important American artists of the twentieth century. A wide-ranging and prolific composer, Zappa created a catalogue over the course of his lifetime that includes several hundred titles in a vast array of genres, ranging from pop music to classical music1. The fiercely independent Zappa (he categorized himself politically as a “Practical Conservative2”) composed, wrote the lyrics for, and performed (mostly on guitar) works with his own band, as well as with other formations, which he directed and recorded in his own studio, and distributed mostly through his own label. The impressive number of interviews he gave over the course of his career constituted a kind of “customer service” for his music, and through them he made a name for himself as a scathing critic of American society in general and of mass culture in particular. Toward the end of his life, he even considered entering electoral politics.

While Zappa’s critical stance may be linked to the Pop Art movement, he is above all known as one of the figureheads of the “freak scene” – a movement that emphasized marginality and embraced the idea of defining oneself outside the bounds and mores of a mainstream society whose values it refused. Zappa’s work nurtured eclecticism in all its forms, and was characterized by the tensions that emerged by placing contradictory elements in relation with one another – he often compared his approach to composing (a piece, a program, etc.) to the work of the American sculptor Alexander Calder, whose mobiles balanced large, lightweight objects against smaller, very dense ones: “So in my case,” Zappa explained, “I say, “A large mass of any material will ‘balance’ a smaller, denser mass of any material, according to the length of the gizmo it’s dangling on, and the ‘balance point’ chosen to facilitate the danglement3”. Rejecting the idea of a hierarchy of values, Zappa spent his life mixing and playing with wildly diverse aesthetics, ultimately producing a singular body of work that remained steadfastly faithful to its own conceptual continuity, despite the seeming miscellany of its constituent parts.

The basic blueprints

It would be impossible to judge Zappa’s catalogue from a single work, or even an entire period; indeed, the composer considered everything he produced (concerts, recordings, writing, interviews, film creations, etc.) to be part of a whole: a single, large-scale work threaded through with returns to and revisions of and variations on recurring themes, a concept he called “Project/Object.” In 1971, in a text published in Circular4, he wrote, “The basic blueprints were executed in 1962-63. Preliminary experimentation in early and mid-1964. Construction of the project/object began in late 1964. Work is still in progress”.

These blueprints, of course, were sketched against the background of Zappa’s personal education – a music lover from an early age, he took just as keen an interest in Edgard Varèse’s explorations of timbre as he did in the performance techniques of Johnny “Guitar” Watson, and marvelled at the virtuosity and humor that Spike Jones wove into the classical music spoofs he arranged for his City Slickers. By 1962, Zappa had joined several bands, performing as a guitarist with such groups as the Boogie Men (1961), the Masters (1961), and Joe Perrino & The Mellotones (1961-1962) – none of which played original material. Their set lists bored Zappa so thoroughly that he abandoned his instrument for nearly a year. In the early 1960s, Zappa began working at Pal Recording Studio, which he bought a few years later and renamed Studio Z. The recording studio quickly became an “instrument” for him, one that he mastered in all its subtleties: he was renowned throughout his career for his tremendous virtuosity in that field.

At the same time, Zappa began to make a name for himself as a composer; he wrote film scores (The World’s Greatest Sinner and Run Home, Slow – see the “biography” tab) and was a guest on the Steve Allen Show, a popular television variety show, where he conducted the show’s orchestra in an improvisational piece titled Concerto For Two Bicycles, Pre-Recorded Tape & Instrumental Ensemble (March 1963). A few weeks later, he organized a concert of his experimental music (19 May 1963), whose program hints at his influences at that time:

• I. Variables II for Orchestra

• II. Variables I for Any Five Instruments

• III. Opus 5, for Four Orchestras

• IV. Rehearsalism

• V. Three Pieces of Visual Music with Jazz Group

The concert was broadcast live on KPFK Radio (Los Angeles), and in the recording one can hear Zappa presenting a piece by explaining, “The pianist will perform these fragments in any order he feels necessary, and will improvise freely upon them”. During the question and answer session that followed the concert, John Cage and Edgard Varèse were evoked, both of whom remained major influences for Zappa (as were Stravinsky and Webern), and in response to a question about “the great masters of the past of music” the young composer explained candidly:

“I know absolutely nothing about any composers before the twentieth century. I have a very unusual type musical background. It’s practically nil. I taught myself what I know—whatever that is—about music. And my own personal tastes and what I listen to do not include very much tonal music of that type. But I’ll tell you what I do like. I’m a great fan of rhythm and blues, and I like rock & roll. And I like folk music. But I don’t like Schubert, and I don’t like Brahms, and I don’t like things like that. I don’t like Beethoven—a whole lot5”.

In 1964, Zappa headed a R&B trio called The Muthers; in 1965, he fronted a quintet called The Soul Giants, which soon became a quartet and was renamed The Blackouts (using the name of his first band, formed during his high school years), and then Captain Glasspack & His Magic Mufflers. Finally, on Mother’s Day (9 May 1965), the band officially changed its name to The Mothers.

The Mothers

It was at this point that Zappa’s career as a public figure really began: at twenty-four, he had already developed a firm understanding of how the music business worked, and while he was aware that the greater public did not share his taste in experimental music, this awareness did nothing to dampen his desire to compose it; quite to the contrary. Throughout his life, he looked for ways to “educate” his audiences6 by introducing them to the composers he so admired. In a similar vein, he maintained a kind of Brechtian distance from them, remaining in constant dialogue with his audience as a way to shorten the distance between the stage and the audience members, between the “great musician” and his public.

Zappa lived on the West Coast in an era when the entertainment industry was beginning to take notice of Western youth culture, in large part thanks to the growth of the hippie movement. This receptiveness made the times particularly favourable to Zappa and his bandmates, in concert and on record. Freak Out! (1966), his first album, released with what was now The Mothers of Invention, was a double album7 that offered a taste of nearly everything that would define him as a composer: pop music parodies (“Go Cry On Somebody Else’s Shoulder”), vitriolic critiques of American society (“Hungry Freaks,” “Daddy”), guitar-heavy blues (“Trouble Every Day”), and highly contemporary experimental music (“The Return Of The Son Of Monster Magnet”). In the 180 names listed as influences for the Mothers in the liner notes, Zappa also noted his desire to abolish hierarchies, citing composers of “serious music” (Pierre Boulez, Charles Ives, Mauricio Kagel, Luigi Nono, Leo Ornstein, Maurice Ravel, Arnold Schoenberg, Roger Sessions, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Igor Stravinsky, Edgard Varèse, Anton Webern), alongside pop singers and jazz musicians (Richard Berry, Eric Dolphy, Bob Dylan, Buddy Guy, Charles Mingus, Elvis Presley), producers and managers (Brian Epstein, Phil Spector, Tom Wilson), painters and authors (Salvador Dali, James Joyce) and many others, a number of whom remain unknown.

In 1966, Zappa began dividing his time between months-long international tours and periods of intensive daily rehearsal with whatever ensemble he was playing with at the time. With the Mothers of Invention (who went back to being The Mothers in 1971) and, starting in 1976, with an ensemble of musicians that accompanied him under no particular name, Zappa developed highly unusual techniques as a musical director and conductor: his musicians played works with no scores that were highly codified, but contained improvisational sections. These pieces might be modified at any moment depending on Zappa’s inspirations (following a principle he named AAAFNRAA, or “Anything, Any Time, Anywhere, For No Reason At All8”). The fact that his musicians were not always trained to read music forced Zappa to develop a language of gestures and instructions (blow like this, play in the style of so-and-so, etc.) that colors his whole catalogue, almost as if he were attempting to establish a unified field theory of musical genres. About the album Cruising With Ruben & The Jets (1968), in which he returned through his own compositions to the R&B and Doo-Wop of his teenage years, Zappa explained, “I conceived that album along the same lines as the compositions in Stravinsky’s neoclassical period. If he could take the forms and clichés of the classical era and pervert them, why not do the same with rules and regulations applied to doo-wop in the fifties9?”

And indeed, the album seems at first listen to be composed in the style Zappa purported to imitate, but the attentive ear cannot miss numerous anachronisms in, for example, the production and the chord progressions. One also notes a certain playful misappropriation, in a sung quotation of the beginning of the Rite of Spring at the end of Fountain of Love. Speaking of the album Uncle Meat (1969 — linked to a film project realized much later, in 1988), Zappa mentioned the influence of Conlon Nancarrow, whose shadow hovers over the work Zappa did later on with the Synclavier, a sampling system designed in the late 1970s by Jon Appleton and his colleagues at Dartmouth College, and which Zappa was one of the first people to acquire (1982). He used the Synclavier to compose works much closer to the world of contemporary art music than to pop music, particularly after the abrupt end of what would turn out to be his last rock music tour, in 1988.

The major projects

The Mothers in their various iterations were a part of the “pop world,” discussed in the “pop media” and performing “pop concerts,” but the constant references to “serious music” running through their “pop music” meant that Zappa and his bands remained marginal, eccentric – freaks, in other words, for fans of either type of music.

Zappa’s major projects that called on classically trained musicians were:

- Lumpy Gravy(Verve, 1968 - Zappa Records, 2009 “original version”) – Zappa’s first solo album, in which he conducted an orchestra of more than 40 musicians, the Abnuceals Emuukha Electric Symphony Orchestra & Chorus.Lumpy Gravy was originally a nine-part piece that lasted 22 minutes (“original” or Capitol version). Conflict over the contract forced Zappa to rework the piece in two parts of 31 minutes in length (released by Verve).

- Music For Electric Violin And Low Budget Orchestra(onKing Kong: Jean-Luc Ponty Plays The Music Of Frank Zappa, Pacific Jazz, 1970) – Zappa revisited this piece in 1975 under the titleRevised Music For Guitar And Low Budget Orchestra with other musicians, including a new incarnation of the Abnuceals Emuukha Electric Orchestra (on “Studio Tan”, DiscReet, 1978).

- Frank Zappa’s 200 Motels(Bizarre/United Artists, 1971) – An ambitiously large-scale project that was also linked to a feature-length film, in which the Mothers of Invention share the stage with other performers, including the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Elgar Howarth. It should be noted that a concert, held on 25 October 1968 at the Royal Festival Hall of London with an orchestra made up of members of the BBC Symphony Orchestra (documented onAhead Of Their Times, Barking Pumpkin, 1993) and another concert held on 15 May 1970 at the Pauley Pavilion (UCLA) with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra (conducted by Zubin Metha), both laid the groundwork for this project.

- Orchestral Favorites (DiscReet, 1979) – An album of two concerts by the second incarnation of the Abnuceals Emuukha Electric Orchestra (conducted by Michael Zearott) on 18 and 19 September 1975 in UCLA’s Royce Hall. It contains some of Zappa’s most successful meldings of performances by “pop” musicians with “standard” instrumental ensembles (its version of “Bogus Pomp”, very different from the one later recorded by the London Symphony Orchestra, deserves special mention). Drums, bass, and solo electric guitar considerably expand the orchestra’s already broad palette of timbres (4 percussionists, 2 violins, viola, cello, harp, 12 brass instruments, 11 woodwinds, as well as guest appearances by soprano saxophone, harmonica, and organ). This type of ensemble appears to be the ideal vehicle for Zappa’s hybrid musical creations.

- London Symphony Orchestra (Barking Pumpkin, vol. 1, 1983 - vol. 2, 1987) – Conducted by Kent Nagano, for his first-ever commercial recording. It features 101 musicians, plus the drummer (Chad Wackerman) and the percussionist (Ed Mann) from Zappa’s rock group, as well as a clarinet soloist (David Ocker).

- Boulez Conducts Zappa: The Perfect Stranger(Angel, 1984) – Here, the Ensemble Intercontemporain, conducted by Pierre Boulez, performed the first recording of “The Perfect Stranger,” as well as “Naval Aviation in Art?” (already recorded onOrchestral Favorites) and “Dupree’s Paradise” (which had already been performed in concert by Zappa’s rock group). This is the first album to include Zappa’s work on the Synclavier (four pieces performed by the Barking Pumpkin Digital Gratification Consort). Zappa described the album as containing seven pieces of dance music written in a “preposterously non-modern” style. Other electronic creations on the Synclavier can be found onFrank Zappa Meets The Mothers Of Prevention(1985),Jazz From Hell(1986),Civilization Phaze III(1994, with samples of members of the Ensemble Modern) andFeeding The Monkies At Ma Maison (2011), among others.

- The Yellow Shark(Barking Pumpkin, 1993) – this was Frank Zappa’s last album, a kind of bequest: it documents his last appearance on stage, conducting the Ensemble Modern, with a piece composed on the Synclavier and reputed to be “unplayable”:G-Spot Tornado(the other pieces, recorded in concert in September 1992 in Frankfurt, Berlin, and Vienna, are conducted by Peter Rundel). The albumEverything Is Healing Nicely (EIHN), which was released in 1999, documents the encounters leading up to the project.

200 Motelsis part of what is known as Zappa’s “vaudeville period”, when Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan were the lead singers in the Mothers. With their extensive improvisational abilities and surprising vocal talent, the duo made it possible for Zappa to play with a highly personal form of musical theatre. Probably the best example from this period is the epic “Billy The Mountain” (from the albumJust Another Band From L.A., 1972), and the composer’s greatest success in this genre wasThe Adventures Of Greggery Peccary, an extraordinary feat of studio production for which he performed all the vocals (Studio Tan— reprised in 2002 by the Ensemble Modern, conducted by Jonathan Stockhammer, with vocals by David Moss and Omar Ebrahim). This vocal work, which he worked on extensively with his rock band, led Zappa to compose the operaJoe’s Garage(1979) and the musicalThing-Fish (1984), both of which offered radical new takes on their respective genres – and neither of which Zappa ever succeeded in staging, due to high production costs.

“Does humor belong in music?10”, Zappa demanded in the title of an album (and a film) in 1985 that documented the concerts in his 1984 tour. There is no doubt that the composer acquired many detractors when he answered with a resounding “Yes!” It was this humor that allowed him to spoof and play with so many musical forms that many of his contemporaries believed to be immutable (and incompatible!) – but it was also this humor that held up a clown mask that succeeded in hiding Zappa’s talent from many observers. “Without deviation (from the norm), progress is not possible11”, Zappa said, and it was indeed transgression, pastiche, satire, and all forms of deviation and redirection that became his norm. Zappa’s rock band was just as likely to perform Bartók, Stravinsky, or Varèse as it was to premiere compositions that would later be recorded by the Ensemble intercontemporain or the London Symphony Orchestra.

*

With one foot in the world of rock and roll and the other in the world of “serious music,” Zappa lived the close of the twentieth century as a kind Doctor Jekyll – but one who was good friends with his Mister Hyde: each of his productions bore the mark of both worlds and all of them defy any attempt at categorization. As he explained in his autobiography:

“Thanks to songs like “Dinah Moe Humm,” “Titties & Beer,” and “Don’t Eat The Yellow Snow,” I managed to accumulate enough cash to bribe a group of drones to grind its way through pieces like “Mo ‘n Herb’s Vacation,” “Bob in Dacron,” and “Bogus Pomp (eventually released on London Symphony Orchestra, Volumes I and II) […]12”.

Postmodern icon, star of jazz and progressive rock, iconoclastic artist, and eternal freak, Frank Zappa built a catalogue that is terribly difficult to describe in a few paragraphs and that richly deserves the interest that it has increasingly sparked since his death. This posthumous recognition is more than a little ironic for a composer who systematically included this quote from Edgard Varèse on the covers of his early Mothers of Invention Albums: “The present day composer refuses to die13”.

- A full list is available here: < https://www.donlope.net/fz/songs/index.html > (link verified 3 January 2022).

- Zappa, Frank, with Peter Occhiogrosso, The Real Frank Zappa Book, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1989, p. 315.

- The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 162.

- Originally published by Warner/Reprise Records, “Hey Hey Hey, Mister Snazzy Exec!,” in Circular, vol. 3, n°29, 20 September 1971. Text available here: https://www.afka.net/Articles/1971-09_Circular.htm (link verified 3 January 2022).

- Transcription by Román García Albertos and Charles Ulrich on the website Information Is Not Knowledge: https://www.donlope.net/fz/radio/1963_KPFK.html (link updated 3 January 2022).

- Nathalie Gatti describes Zappa’s approach to teaching in “Frank Zappa, l’esthétique d’un nomade,” in Circuit, musiques contemporaines (2004).

- Blonde on Blonde, Bob Dylan’s seventh album, is considered to be the first double album in the history of rock music. It was released on 16 May 1966. Freak Out! was released on 27 June that same year.

- The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 163

- The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 188.

- Does Humor Belong In Music?, EMI, 1986.

- The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 185.

- The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 148.

- Varese’s words were included in the manifesto of the International Composers’ Guild (1921).

© Ircam-Centre Pompidou, 2013

- Chamber music

- Dupree's Paradise arrangement by Jon Nelson for brass quintet and drums (), 4 mn, Munchkin Music

- Harry You're a Beast / Orange County Lumber Truck arrangement by Jon Nelson for brass quintet and drum kit (), 60 s, Munchkin Music

- Questi Cazzi Di Piccione for string quartet (), 3 mn, Munchkin Music

- T'Mershi Duween arrangement by Jon Nelson for brass quintet and drums (), 2 mn, Munchkin Music

- Number 6 for wind quintet (1981), 2 mn 6 s, Munchkin Music

- Wind Quintet for wind quintet (1984), 43 s, Munchkin Music

- III Revised arrangement for string quintet (1985-1992), 2 mn, Munchkin Music

- None of the Above arrangement for string quintet (1985-1992), 2 mn, Munchkin Music

- Instrumental ensemble music

- The Dog Breath Variations for wind ensemble and rock band (1970), 6 mn, Munchkin Music

- The Dog Breath Variations/Uncle Meat for ensemble, transcription by Ali N. Askin (1970), 6 mn, Munchkin Music

- Revised Music for Low Budget Symphony Orchestra for orchestra, transcription by Ali N. Askin and Bruce Fowler (1972), 8 mn, Munchkin Music

- Bob in Dacron for orchestra (1975), 12 mn, Munchkin Music

- Pedro's Dowry for chamber orchestra (1975), 8 mn, Munchkin Music

- Sad Jane for orchestra (1975), 10 mn, Munchkin Music

- The Black Page arrangement for ensemble by Walter Boudreau (1976), 6 mn, Inédit [program note]

- Naval Aviation in Art? for ensemble (1977), 3 mn, Munchkin Music

- Mo 'n Herb's Vacation for orchestra (1979), 28 mn, Munchkin Music

- Envelopes for symphony orchestra (1981), 3 mn, Munchkin Music

- Envelopes for wind and rock band ensemble (1981), 3 mn, Munchkin Music

- Pedro's Dowry for orchestra (1983), 10 mn, Munchkin Music

- Strictly Genteel for orchestra (1983), 7 mn, Munchkin Music

- Dupree's Paradise for orchestra (1982-1984), 8 mn, Munchkin Music

- Sinister Footwear for orchestra (1984), 25 mn, Munchkin Music

- The Perfect Stranger for orchestra (1984), 13 mn, Munchkin Music

- Times Beach third movement transcribed by Ali Askin for ensemble (1985), 4 mn, Munchkin Music

- The Beltway Bandits for ensemble (1986), 4 mn, Munchkin Music

- Be‐Bop Tango for ensemble, transcription by Ali N. Askin (1972-1992), 4 mn, Munchkin Music

- G-Spot Tornado for ensemble, transcription by Ali N. Askin (1992), 5 mn, Munchkin Music

- Get Whitey for orchestra (1992), 7 mn, Munchkin Music

- Outrage at Valdez for ensemble (1990-1992), 3 mn, Munchkin Music

- The Girl in the Magnesium Dress for ensemble (1992), 5 mn, Munchkin Music

- Peaches En Regalia arrangement for ensemble by Ali N. Askin, 2000 (1969, 2000), 3 mn, Munchkin Music

- Vocal music and instrument(s)

- I'm Stealing the Room for solo voices, choir and orchestra (1969), 5 mn about , Munchkin Music

- Penis Dimension for solo voices, choir and orchestra (1969), 5 mn about , Munchkin Music

- The Adventures of Greggery Peccary transcription by Ali N. Askin for male voice, two actors, narrator and orchestra (1974), 25 mn, Munchkin Music

- Bogus Pomp orchestration by David Ocker for children's voices, mixed choir and orchestra (1983), 25 mn, Munchkin Music

Catalog sources and details

Pour un catalogue complet de l’œuvre de Zappa (incluant improvisations, compositions, interprétations et n’opérant pas de disssociations, disques / partitions), voir la liste complète : discographie: http://globalia.net/donlope/fz/lyrics/index.html ou liste des œuvres http://globalia.net/donlope/fz/songs/index.html (liens vérifiés en juillet 2013).

Nous ne listons ici que les œuvres existant ou ayant existé sous forme de partition de la main de Frank Zappa. Nous nous basons sur la liste de l’éditeur (Schott) complétée par Réjean Beaucage.

Orchestrations de Walter Boudreau

Peaches en Regalia(Hot Rats, 1970) pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen (2 claviers, 2 perc., basse élec., batterie, saxophones, flûte)

The Black Page No.1(Live in new York, 1976)

- pour quatuor à cordes

- pour quatuor de violoncelles

- pour quatuor de saxophones

- pour l’ensemble de la SMCQ

The Black Page No.2(Live in new York, 1976) pour l’Ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

Zomby Woof(Overnite Sensation, 1973)

- pour quatuor à cordes

- pour quatuor de violoncelles

- pour quatuor de saxophones

- pour quintette de cuivres & batterie

- pour La Pièta (ensemble à cordes + piano)

Drowning With Interlude(Ship arriving too late…, 1982) pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

Envelope(Ship arriving too late…,1982) pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

Teenage Prostitute(Ship arriving too late…,1982)

- pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

- pour l’ensemble vocal féminin Héliade

The Girl in the Magnesium Dress(Boulez conducts Zappa, 1984) pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

Penis Dimension(200 Motels, 1971)

- pour l’Ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

- pour l’Ensemble vocal féminin Héliade

Dirty Love(Overnite Sensation, 1973)

- pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

- pour l’ensemble vocal féminin Héliade

Outside Now Again(Boulez conducts Zappa, 1984) pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

Alien Orifice(F.Z. meets the Mothers of prevention, 1984) pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

- 2000

- Peaches En Regalia arrangement for ensemble by Ali N. Askin, 2000, 3 mn, Munchkin Music

- 1992

- Be‐Bop Tango for ensemble, transcription by Ali N. Askin, 4 mn, Munchkin Music

- G-Spot Tornado for ensemble, transcription by Ali N. Askin, 5 mn, Munchkin Music

- Get Whitey for orchestra, 7 mn, Munchkin Music

- III Revised arrangement for string quintet, 2 mn, Munchkin Music

- None of the Above arrangement for string quintet, 2 mn, Munchkin Music

- Outrage at Valdez for ensemble, 3 mn, Munchkin Music

- The Girl in the Magnesium Dress for ensemble, 5 mn, Munchkin Music

- 1986

- The Beltway Bandits for ensemble, 4 mn, Munchkin Music

- 1985

- Times Beach third movement transcribed by Ali Askin for ensemble, 4 mn, Munchkin Music

- 1984

- Dupree's Paradise for orchestra, 8 mn, Munchkin Music

- Sinister Footwear for orchestra, 25 mn, Munchkin Music

- The Perfect Stranger for orchestra, 13 mn, Munchkin Music

- Wind Quintet for wind quintet, 43 s, Munchkin Music

- 1983

- Bogus Pomp orchestration by David Ocker for children's voices, mixed choir and orchestra, 25 mn, Munchkin Music

- Pedro's Dowry for orchestra, 10 mn, Munchkin Music

- Strictly Genteel for orchestra, 7 mn, Munchkin Music

- 1981

- 1979

- Mo 'n Herb's Vacation for orchestra, 28 mn, Munchkin Music

- 1977

- Naval Aviation in Art? for ensemble, 3 mn, Munchkin Music

- 1976

- The Black Page arrangement for ensemble by Walter Boudreau, 6 mn, Inédit [program note]

- 1975

- Bob in Dacron for orchestra, 12 mn, Munchkin Music

- Pedro's Dowry for chamber orchestra, 8 mn, Munchkin Music

- Sad Jane for orchestra, 10 mn, Munchkin Music

- 1974

- The Adventures of Greggery Peccary transcription by Ali N. Askin for male voice, two actors, narrator and orchestra, 25 mn, Munchkin Music

- 1972

- Revised Music for Low Budget Symphony Orchestra for orchestra, transcription by Ali N. Askin and Bruce Fowler, 8 mn, Munchkin Music

- 1970

- The Dog Breath Variations for wind ensemble and rock band , 6 mn, Munchkin Music

- The Dog Breath Variations/Uncle Meat for ensemble, transcription by Ali N. Askin, 6 mn, Munchkin Music

- 1969

- I'm Stealing the Room for solo voices, choir and orchestra, 5 mn about , Munchkin Music

- Penis Dimension for solo voices, choir and orchestra, 5 mn about , Munchkin Music

- Date de composition inconnue

- Dupree's Paradise arrangement by Jon Nelson for brass quintet and drums, 4 mn, Munchkin Music

- Harry You're a Beast / Orange County Lumber Truck arrangement by Jon Nelson for brass quintet and drum kit, 60 s, Munchkin Music

- Questi Cazzi Di Piccione for string quartet, 3 mn, Munchkin Music

- T'Mershi Duween arrangement by Jon Nelson for brass quintet and drums, 2 mn, Munchkin Music

Catalog source(s)

Pour un catalogue complet de l’œuvre de Zappa (incluant improvisations, compositions, interprétations et n’opérant pas de disssociations, disques / partitions), voir la liste complète : discographie: http://globalia.net/donlope/fz/lyrics/index.html ou liste des œuvres http://globalia.net/donlope/fz/songs/index.html (liens vérifiés en juillet 2013).

Nous ne listons ici que les œuvres existant ou ayant existé sous forme de partition de la main de Frank Zappa. Nous nous basons sur la liste de l’éditeur (Schott) complétée par Réjean Beaucage.

Orchestrations de Walter Boudreau

Peaches en Regalia(Hot Rats, 1970) pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen (2 claviers, 2 perc., basse élec., batterie, saxophones, flûte)

The Black Page No.1(Live in new York, 1976)

- pour quatuor à cordes

- pour quatuor de violoncelles

- pour quatuor de saxophones

- pour l’ensemble de la SMCQ

The Black Page No.2(Live in new York, 1976) pour l’Ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

Zomby Woof(Overnite Sensation, 1973)

- pour quatuor à cordes

- pour quatuor de violoncelles

- pour quatuor de saxophones

- pour quintette de cuivres & batterie

- pour La Pièta (ensemble à cordes + piano)

Drowning With Interlude(Ship arriving too late…, 1982) pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

Envelope(Ship arriving too late…,1982) pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

Teenage Prostitute(Ship arriving too late…,1982)

- pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

- pour l’ensemble vocal féminin Héliade

The Girl in the Magnesium Dress(Boulez conducts Zappa, 1984) pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

Penis Dimension(200 Motels, 1971)

- pour l’Ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

- pour l’Ensemble vocal féminin Héliade

Dirty Love(Overnite Sensation, 1973)

- pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

- pour l’ensemble vocal féminin Héliade

Outside Now Again(Boulez conducts Zappa, 1984) pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

Alien Orifice(F.Z. meets the Mothers of prevention, 1984) pour l’ensemble Dangerous Kitchen

Discographie sélective

Pour une discographie complète se référer au site de Román García Albertos, http://globalia.net/donlope/fz/lyrics/index.html (lien vérifié en juillet 2013).

Avec The Mothers of Invention

- Freak Out!, 2 microsillons, 1966, Verve/MGM, V/V6-5005-2.

- Uncle Meat, 2 microsillons, 1969, Bizarre/Reprise, 2MS 2024.

- Burnt Weeny Sandwich, microsillon, 1970, Bizarre/Reprise, RS 6370.

- Weasels Ripped My Flesh, microsillon, 1970, Bizarre/Reprise, MS 2028.

- Frank Zappa’s 200 Motels, The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, direction : Elgar Howarth, 2 microsillons, 1971, Bizarre/United Artists, UAS 9956.

- One Size Fits All, microsillon, 1975, DiscReet, DS 2216.

Avec The Mothers

- Fillmore East - June 1971, microsillon, 1971, Bizarre/Reprise, MS 2042.

- The Grand Wazoo, microsillon, 1972, Bizarre/Reprise, MS 2093.

- Roxy & Elsewhere, 2 microsillons, 1974, DiscReet, 2DS 2202.

Avec The Mothers et Captain Beefheart

- Bongo Fury, microsillon, 1975, DiscReet, DS 2234.

Avec le Hot Rats Ensemble

- Waka/Jawaka, microsillon, 1972, Bizarre/Reprise, MS 2094.

Sous son seul nom

- Hot Rats, microsillon, 1969, Bizarre/Reprise, RS 6356.

- Apostrophe (‘), microsillon, 1974, DiscReet, DS 2175.

- In New York, 2 microsillons, 1978, DiscReet, 2D 2290.

- Joe’s Garage Act I, II & III, 3 microsillons, 1979, Zappa Records, SRZ-1-1603 et SRZ-2-1502.

- Shut Up ‘N Play Yer Guitar, 3 microsillons, 1981, Barking Pumpkin, BPR 1111; BPR 1112; BPR 1113.

- Ship Arriving Too Late To Save A Drowning Witch, microsillon, 1982, Barking Pumpkin, FW 38066.

- London Symphony Orchestra Vol. I, Kent Nagano, dir., microsillon, 1983, Barking Pumpkin, FW 38820.

- Boulez conducts Zappa: The Perfect Stranger, Ensemble intercontemporain, direction : Pierre Boulez, microsillon, 1984, Angel, DS-38170.

- Them Or Us, 2 microsillons, 1984, Barking Pumpkin, SVBO-74200.

- Thing-Fish, 3 microsillons, 1984, Barking Pumpkin, SKCO-74201.

- Frank Zappa Meets The Mothers Of Prevention, microsillon, 1985, Barking Pumpkin, ST-74203.

- Does Humor Belong In Music?, CD, 1986, EMI, CDP 7 46188 2.

- Jazz From Hell, microsillon,1986, Barking Pumpkin, ST-74205.

- London Symphony Orchestra Vol. II, direction : Kent Nagano, microsillon, 1987, Barking Pumpkin, SJ-74207.

- You Can’t Do That On Stage Anymore Vol. 1, 2 cds, 1988, Rykodisc, RCD 10081/82.

- You Can’t Do That On Stage Anymore Vol. 2, 2 cds, 1988, Rykodisc (RCD 10083/84)

- You Can’t Do That On Stage Anymore Vol. 3*, 2 cds, 1989, Rykodisc (RCD 10085/86)

- Make A Jazz Noise Here, 2 CD, 1991, Barking Pumpkin (D2 74234)

- You Can’t Do That On Stage Anymore Vol. 4, 2 cds, 1991, Rykodisc (RCD 10087/88)

- You Can’t Do That On Stage Anymore Vol. 5, 2 cds, 1992, Rykodisc (RCD 10089/90)

- You Can’t Do That On Stage Anymore Vol. 6, 2 cds, 1992, Rykodisc (RCD 10091/92)

- The Yellow Shark, Ensemble Modern, Frank Zappa, direction (1, 19), Peter Rundel, direction (2-18), 1 cd, 1993, Barking Pumpkin, R2 71600.

- Civilization Phaze III, Ensemble Modern, Frank Zappa, direction, 2 cds, 1994, Barking Pumpkin, UMRK 01.

- The Lost Episodes, 1 cd, 1996, Rykodisc, RCD 40573.

- Läther, 3 cds, 1996, Rykodisc, RCD 10574/76.

- Everything Is Healing Nicely, 1 cd, 1999, Barking Pumpkin, UMRK 03.

- The Lumpy Money Project/Object, 3 cds, 2009, Zappa Records, ZR20008.

- Greasy Love Songs, 1 cd, 2010, Zappa Records, ZR20010.

- Feeding The Monkies At Ma Maison, 1 cd, 2011, Zappa Records, ZR20012.

Bibliographie sélective

- Guitar Player Magazine: A Definitive Tribute To Frank Zappa, San Francisco, Miller Freeman, 1994.

- « Frank Zappa - Candid Conversation », Playboy, vol. 40, n° 4, avril 1993, p. 55.

- The Old Masters - Box One, livret du coffret éponyme, Van Nuys, Californie, Barking Pumpkin Records, 1984.

- Réjean BEAUCAGE (sous la dir. de),« Frank Zappa : 10 ans après », Circuit - musiques contemporaines, vol. 14, n° 3, Montréal, Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2004.

- Dominique CHEVALIER, Viva! Zappa, traduction de Matthew Screech, Londres, Omnibus Press, 1986 (édition originale : Paris, Calmann-Levy, 1985).

- Alain DISTER et Urban GWERDER, Frank Zappa et les Mothers of Invention, Paris, Albin Michel, coll. « Rock & Folk », 1975.

- Kelly FISHER LOWE, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, Westport, Praeger, The Praeger Singer-Songwriter Collection, 2006.

- Phil HARDY et Dave LAING, The Faber Companion to 20th-Century Popular Music, Londres, Faber and Faber, 1990.

- Jean-Sébastien MARSAN, Le Petit Wazoo - initiation rapide, efficace et sans douleur à l’œuvre de Frank Zappa, préface de Réjean Beaucage, Montréal, Triptyque, 2010.

- Barry MILES, Frank Zappa In His Own Words, Londres, Omnibus Press, 1993.

- David WALLEY, No Commercial Potential - The Saga of Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention, New York, Outerbridge & Lazard, 1972.

- Frank ZAPPA et Peter OCCHIOGROSSO, The Real Frank Zappa Book, New York, Poseidon Press, 1989.

- Frank ZAPPA et Peter OCCHIOGROSSO, Zappa par Zappa, traduction de Jean-Marie Millet, Paris, L’Archipel, 2000.

Lien Internet

- Román García Albertos, Information Is Not Knowledge, http://globalia.net/donlope/fz (vérifié en juillet 2013).